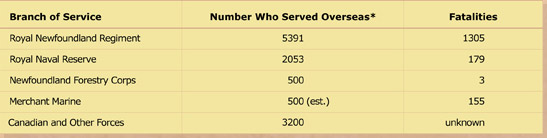

The Great War left its mark on all areas of the colony. Nearly 12000 men left to fight in the war between 1914 and 1918.

Newfoundlanders and Labradorians in the First World War

*These figures do not include 175 women from Newfoundland and Labrador who served overseas as nurses and ambulance drivers during the war.

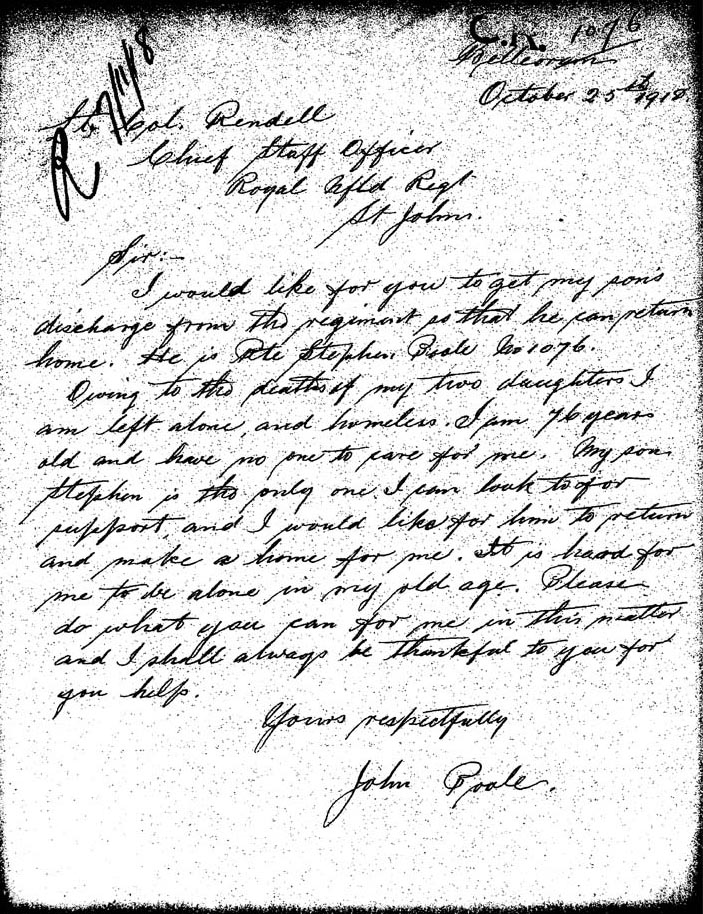

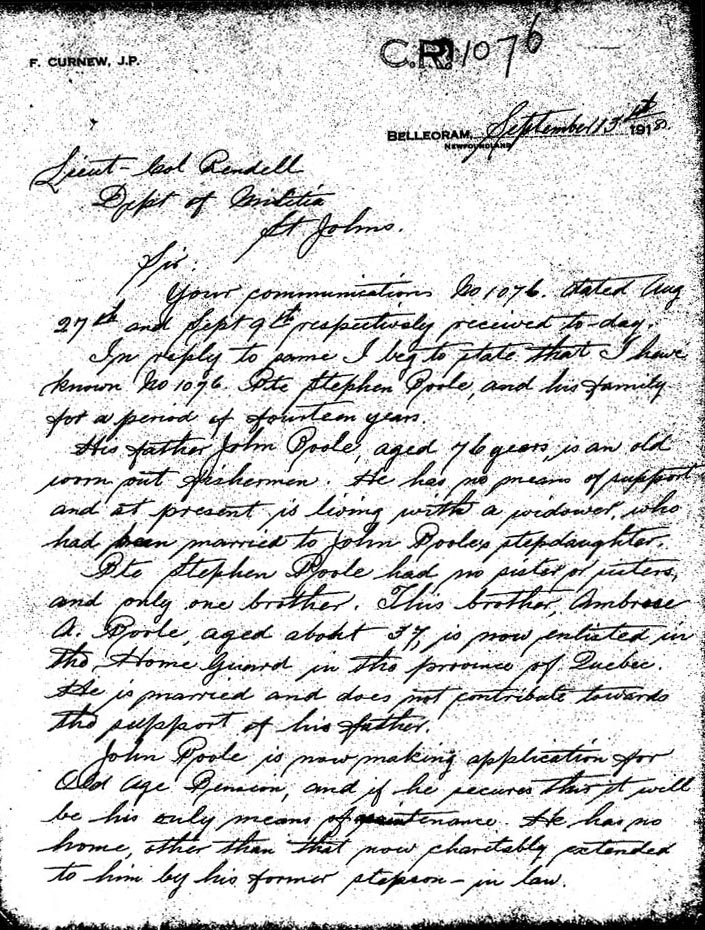

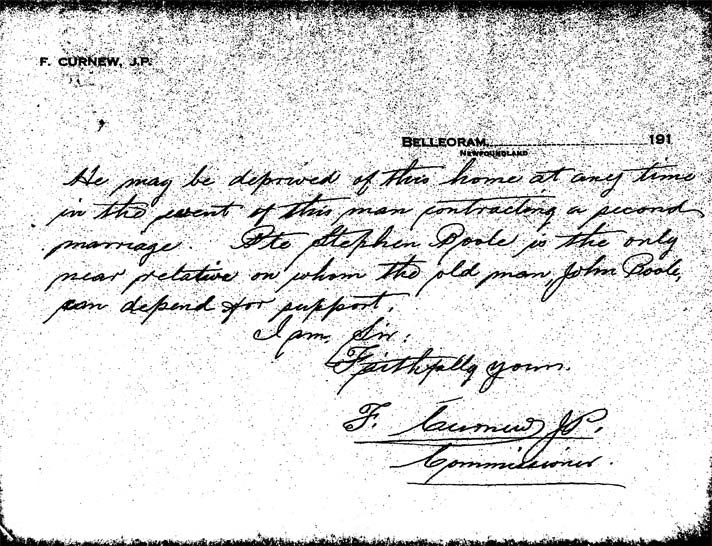

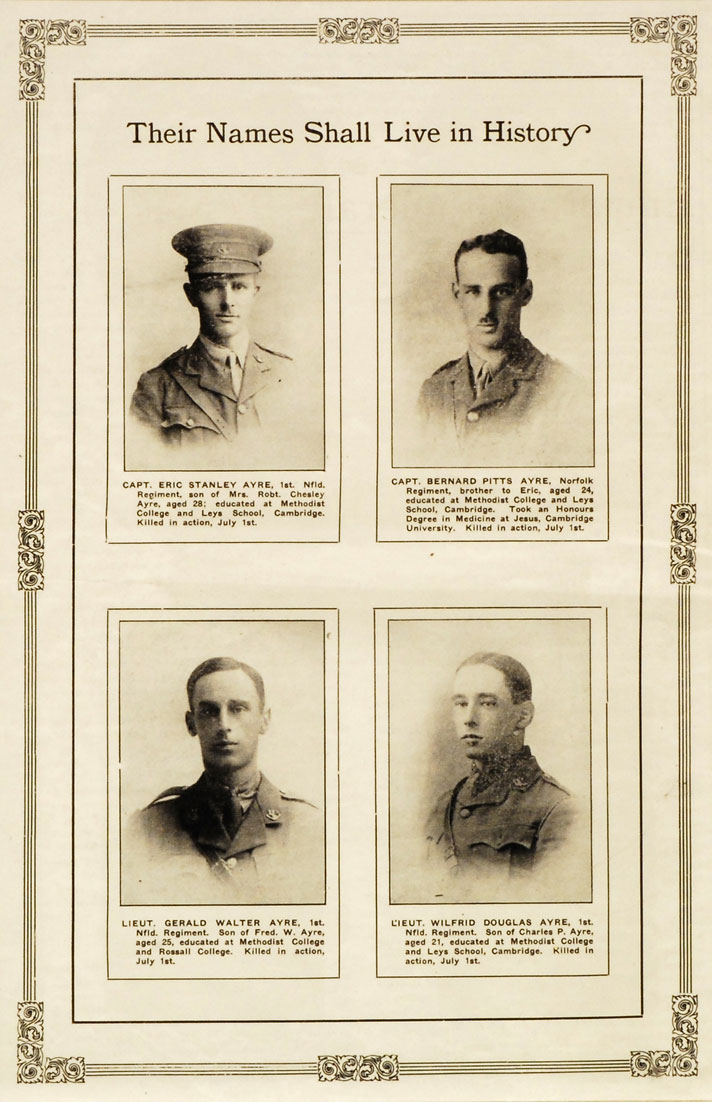

It is difficult to measure (or imagine) the effects of having so many young men, both temporarily and permanently, removed from a society. Some children grew up fatherless. Many parents lost the support they normally would have received from their male children in later years. It also meant part of a generation of potential leaders was lost to Newfoundland and Labrador.

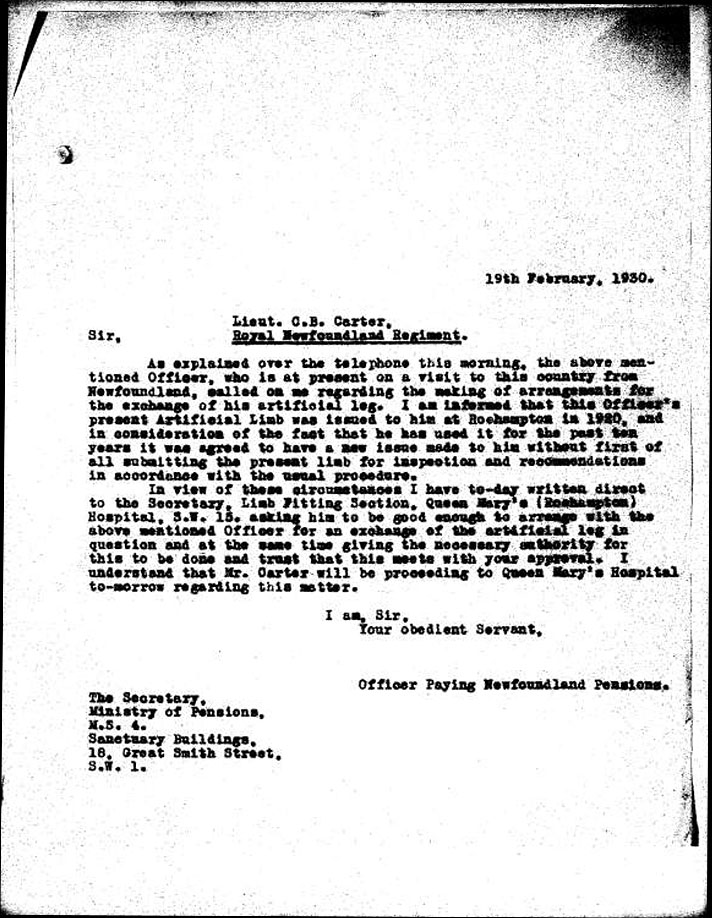

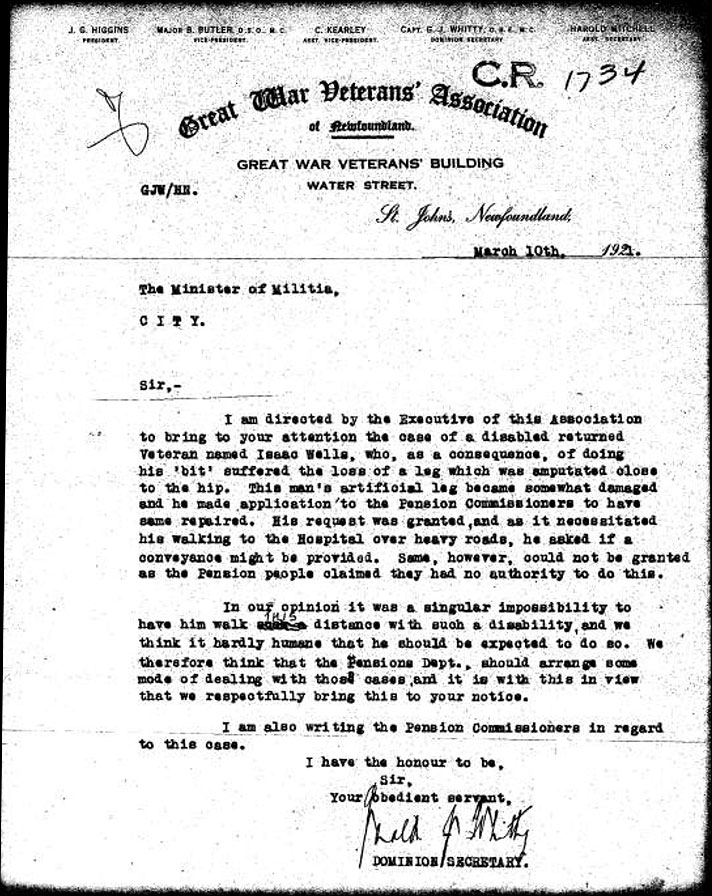

Request for Support

The Rooms Provincial Archives Regimental File #1076

Ayre Family

The Cadet (Catholic Cadet Corps: December 1916, p. 36)

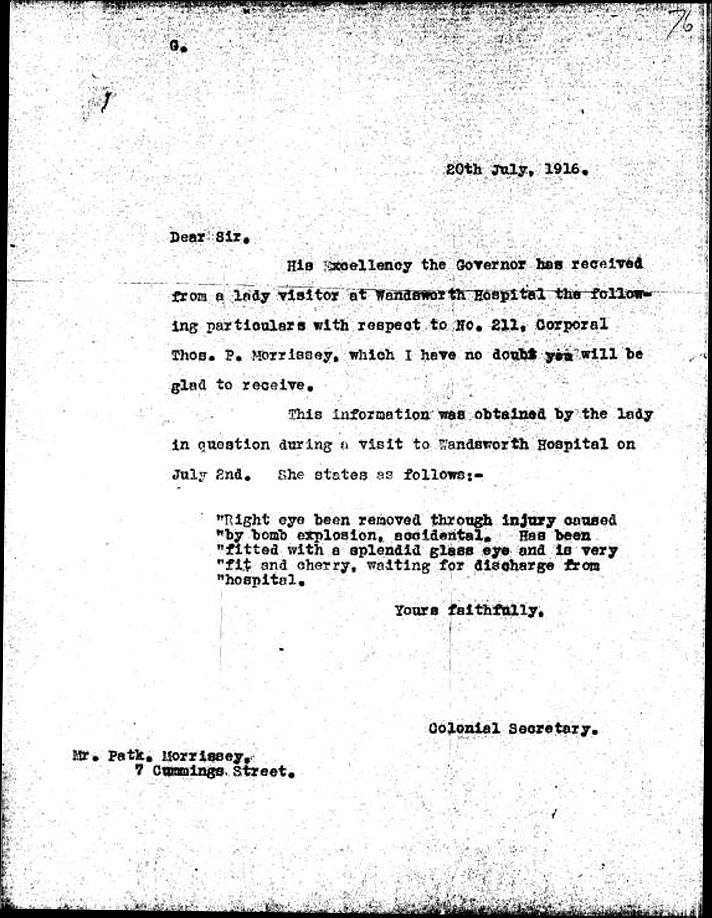

The Rooms Provincial Archives

The challenge for the soldiers and seamen who did return from the war was to fit back into the lives they had left behind. Some were able to return to fishing or their old jobs. But many others — especially those who had left to fight in the war while still in school or who returned with disabilities — found themselves back home without a way to support themselves or their families.

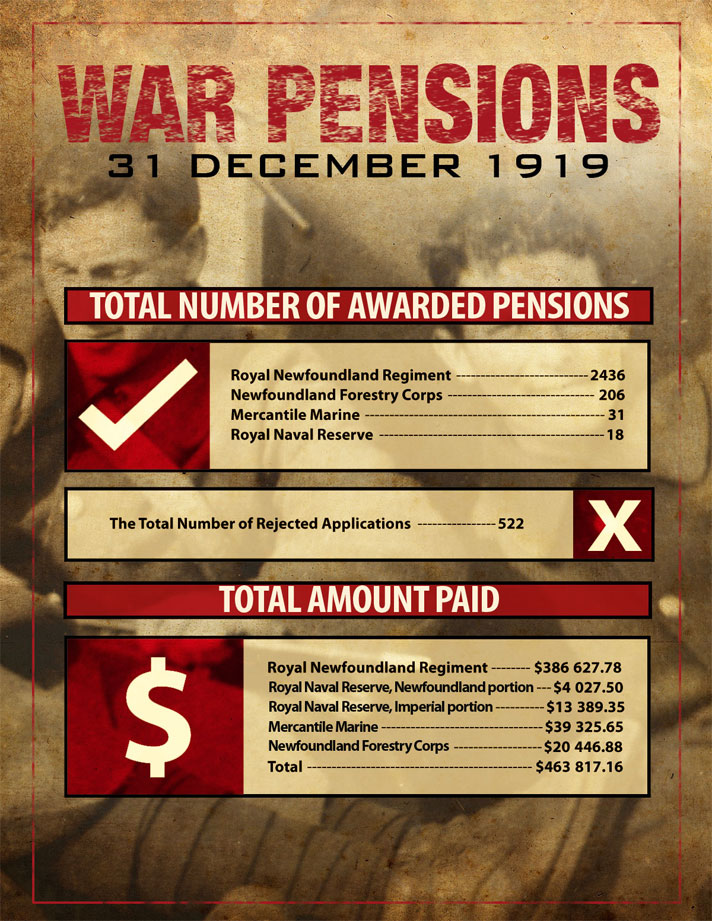

War Pensions

Background Image: The Rooms Provincial Archives VA 79-81.4

Many veterans also suffered psychological effects from the war, including shell shock. This impact is difficult to measure — especially as soldiers were often reluctant to talk of their war experiences. As military historian Richard Gabriel has noted: "Psychiatric breakdown remains one of the most costly items of war when expressed in human terms. In fact, in the First World War there was a greater probability of becoming a psychiatric casualty than of being killed by enemy fire."

To help returning servicemen re-adjust to their lives as civilians, the government created the Civil Re-Establishment Committee in June 1918. The committee had three goals: restore injured men to the best possible state of health; provide vocational training; and assist with job placement.

Medical

The Rooms Provincial Archives

One of the committee's first steps was to set up the "Re-Establishment School" for soldiers with little or no formal education. By 1920, almost 400 returning servicemen had enrolled in the school. In addition, the committee set up an Engineering School, a Nautical Academy, a Woodworking School, and a School of Telegraphy, which provided training for another 400 men. The committee also helped 80 men enroll in other courses or find apprenticeships. To ensure the men were able to take advantage of these programs, the committee paid a retraining allowance.

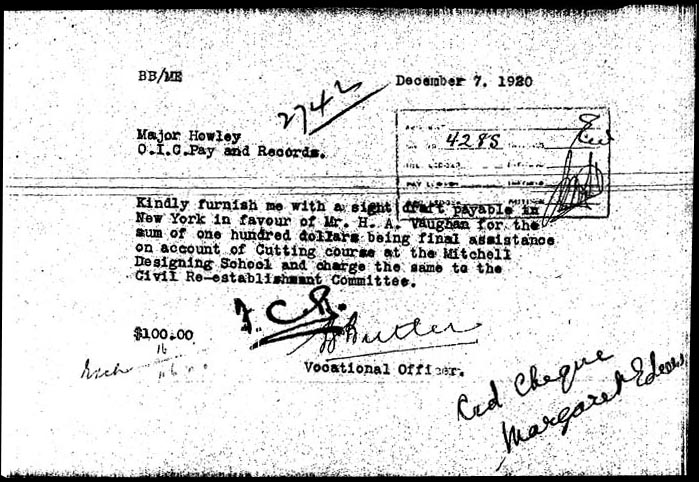

Invoice for Training

The Rooms Provincial Archives Regimental File #2742

Job placement was also an important part of the Civil Re-Establishment Committee's work. Before closing its doors in September 1920, the Committee placed over 1000 ex-servicemen in jobs. It also helped many of them to start their own businesses by loaning them money for equipment and supplies. In total, the Committee spent almost $329 000 administering its various programs.

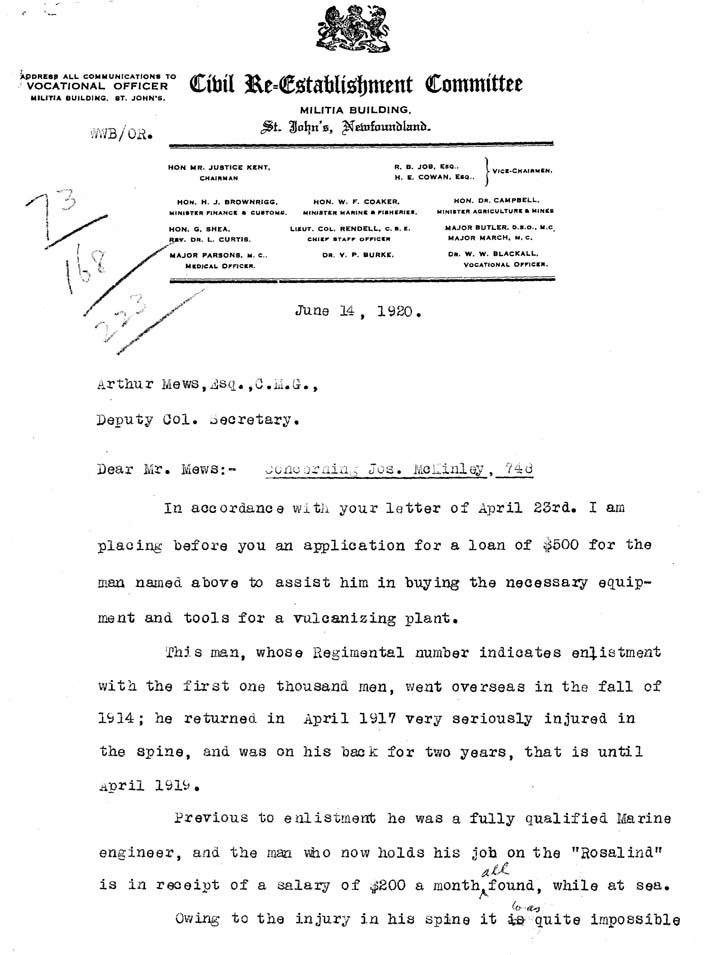

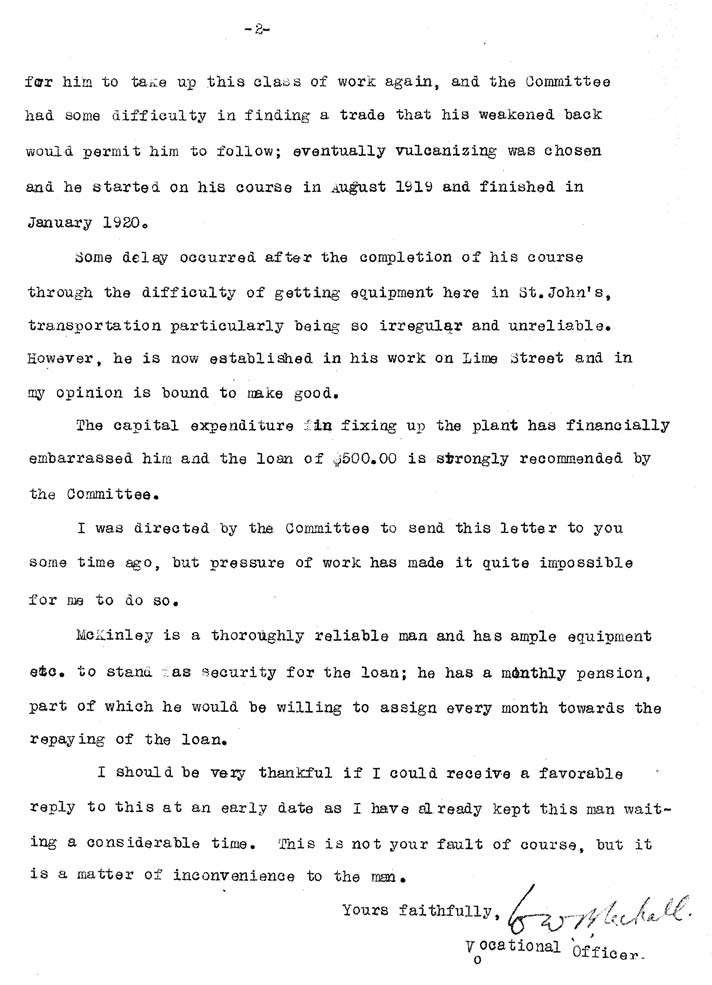

An example of one such man was Joseph McKinley (Regt. # 748) of St. John's. This soldier went overseas in the fall of 1914 and was sent home in 1917 with severe back injuries. Unable to return to work as a Marine Engineer, he approached the Civil Re-Establishment Committee. They trained him in vulcanizing (curing rubber so that it is more durable) and lent him $500 to buy the necessary equipment and tools to set up a vulcanizing business.

Request for Funding

The Rooms Provincial Archives GN2.14.152

Despite the Civil Re-Establishment Committee's efforts, some servicemen still experienced challenges in returning to civilian life. A branch of the Great War Veterans' Association, established in St. John's in August 1918, helped to advocate for these men. This organization worked to increase veterans' pensions and to establish a national war memorial.

While the Association eventually succeeded in both these goals, there were still some veterans who struggled to find work. In 1921, one veteran presented a petition to the government seeking work for the unemployed in St. John's. The ex-soldier, who had only one arm, carried the Union Jack with him as he entered the House of Assembly. He explained that his other arm was in France.

House of Assembly

House of Assembly, Colonial Building, St. John's

Memorial University of Newfoundland Archives and Special Collections Division, Coll. 137, 2.04.001