The Newfoundland Museum: Origin and Development

The Newfoundland Museum: Origins and Development

By John E. Maunder

Fall 1991.

[Originally published in printed form. Interim edition - preliminary notes and observations from a more extensive work in progress.]

At the dawning of the nineteenth century, St. John's, Newfoundland was a rowdy, dirty and disorganized little fishing village and military garrison of about 5000 souls. The indentured poor struggled just to survive. The wealthy and powerful often lived to excess. Governing was strict. Justice was harsh. And, despite the efforts of a few elite private academies and the schools of "The Society for Improving the Conditions of the Poor of St. John's", the town was a literary and cultural wasteland.

In 1807, John Ryan arrived from New Brunswick to begin publication of Newfoundland's first newspaper. It might be argued that his Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser was immediately influential in stimulating some small degree of literary, cultural and social improvement in St. John's. Within months of the paper's first issue, three new schools advertised in its pages. Sometime before 1810, the St. John's Subscription Library was formed - though it only lasted until 1813. In 1816, the Gazette was joined in its endeavours by the first of many future competitors - the Newfoundland Mercantile Journal. Then, in 1820, the Saint John's Library Society was founded. Before long, its members set up a "public" reading room in the Freemason's Tavern.

Gradually, the tradesmen and the other professionals of the rapidly growing town, came to see the advantages of setting up "learned societies", where ideas could be exchanged, knowledge acquired and acquaintances made. By 1827, St. John's could boast its own Mechanics' Society [NOT the same as the later, and parallel, "Mechanics' Institute"].

Gradually, the tradesmen and the other professionals of the rapidly growing town, came to see the advantages of setting up "learned societies", where ideas could be exchanged, knowledge acquired and acquaintances made. By 1827, St. John's could boast its own Mechanics' Society [NOT the same as the later, and parallel, "Mechanics' Institute"].

While some of the early clubs and societies undoubtedly maintained private collections of curiosities - as was the style of the time - the word "museum" did not appear in the Newfoundland literature until 1840. In that year, the newly founded Newfoundland Literary and Scientific Institution identified the formation of a museum as one of its "objects." The following year, the St. John's Reading-Room and Library solicited "specimens in Natural History, Fossils, &c." in anticipation of forming its own museum. It is not known whether either museum was ever assembled.

But, by 1848, the "museum idea" was well-established. Mr. Henry Palmer wrote letters to Governor LeMarchant and to the Secretary of State, using the title "proprietor of a Museum at Saint Johns [sic] Newfoundland." The Agricultural Society boasted a museum, curated by Mr. E.L. Moore - a corresponding member of the Zoological Society of London. And, nothing less than a "public Botanical Garden and Museum" [situated near the Colonial Building] was advertised by horticulturist William Leahy.

In 1849, the St. John's Mechanics' Institute was formed - a sort of subscriber-supported adult education facility for tradesmen and professionals. It too began a museum, and assembled collections of both "natural history" and "apparatus," primarily to provide illustrative examples in support of its extensive series of public lectures. In fact, the Mechanic's Museum grew so quickly that it soon had to be removed to temporary quarters at the Colonial Building. By February of 1852, its natural history section contained 709 specimen-lots, including such diverse curiosities as a stuffed giraffe, a skull and jaw of a Beothuk Indian, two pairs of five-toed-and-webbed chicken's feet [!], and a piece of lava from Mount Vesuvius. But, from the beginning, the Museum was a financial burden to the Mechanics' Institute. Grants from the Legislature helped only to a point.

As the proliferation of "educational and philosophical" institutions continued apace in Newfoundland, it became apparent that duplication of facilities and services was getting out of hand. A first attempt at consolidating resources resulted in the formation of the "St. John's Athenaeum" in 1851 [NOT the same as the later "Athenaeum of 1861"]. The organization - a co-operative effort of the Mechanics' Institute and the St. John's Library and Reading Room, primarily - was simply a building committee and joint-stock company, whose aims were to erect and maintain a multi-use facility to serve the many local learned societies, including their own, and to eventually turn a profit.

That same year, 1851, the prototype of all future "international exhibitions," or "world fairs," was opened at the colossal, purpose-built "Crystal Palace" in London. Countries from all over the globe sent exhibits extolling the virtues of their respective cultural and industrial products and resources. But, alas, Newfoundland's contribution - a single bottle of cod liver oil! - was decidedly undistinguished. The local press responded with derision. To its credit, Newfoundland did manage to assemble a more extensive exhibit for the somewhat smaller "World's Fair of the Works of Industry of all Nations" held at New York in 1853-54. It even won three medals for excellence of exhibits. Prior to being shipped, the whole exhibit was successfully put on display for a few days in St. John's.

Newfoundland's participation in the 1853 exhibition turned out to be a watershed. The Colony had suddenly come to realize the value in promoting its resource and manufacturing potential overseas. The newspapers of the time seem to indicate that the real motivation behind Newfoundland's involvement in the New York exhibition was its halting quest for a Free Trade deal with the United States. In the years that followed, international exhibition became one of the Colony's prime strategies for building both a better commercial base, and a national sense of pride.

This new appreciation for the practical value of exhibitions led to a definite shift toward resource-based, self-promoting exhibits in the museums back home; something that persisted through the turn of the century, as Newfoundland continued to sell itself, and participate in more and more international shows.

After ten years of trying, the shareholders of the "Athenaeum of 1851" had failed in their efforts to erect a building! The costs involved were just too great. A new strategy was needed. In 1861, the "St. John's Young Men's Literary and Scientific Institute," the "St. John's Library and Reading Room", and the "Mechanics' Institute" merged to form a single institution - again called the "St. John's Athenaeum". As part of the deal, the new organization inherited the Mechanics' Museum, much to the dismay of those shareholders more interested in literary things and the balancing of budgets. Inevitably, the Museum became involved in the selection of items for the London International Exhibition of 1862.

The first priority of the NEW Athenaeum, like that of its predecessor, was to secure a favourable property, and to erect a building. In 1863, as an economic measure, the Society decided to dismantle the Mechanics' Museum. It was not prepared, however, for the public outcry that followed. In the end, it agreed to keep any museum specimens found to be in good repair, or of some value. Such a collection would serve as a creditable core for a new museum, should one be placed in "the new building". Mr. E.J. Wyatt agreed to store the collection in the interim.

In 1864, a significant event took place. Alexander Murray was hired to set up a Newfoundland Geological Survey. Murray plunged into his new job with great gusto, and was soon collecting rocks, minerals and fossils from all over the island, and elsewhere. Inevitably, he was asked to provide geological specimens for the Newfoundland exhibit in the Paris international exhibition of 1867. Prior to being shipped overseas, the entire exhibit was displayed for one day in the Colonial Building - to great acclaim.

In 1868, Murray began petitioning government for an "apartment" to house his growing "museum of arranged geological collections". Early in 1871, the Governor gave his support, and a suitable museum space was fitted up, attached to Murray's official residence, the "Engineer's House". The collections of the Newfoundland Geological Survey thus became the foundation for Newfoundland's first government-supported museum. The year before, in 1870, the Government had purchased the "Museum of the Athenaeum". Whether the artifacts from that museum were ever officially transferred to Murray is unclear, but at least some items did eventually end up in the "Geological Museum".

Murray continued to collect geological specimens at a great rate; but his interests, like those of his assistant, James Howley, were quite eclectic. The Museum collections soon exhibited a number of non-geological items, including Beothuk artifacts and remains, a collection of Newfoundland sea shells presented by the German naturalist T.A. Verkrüzen, and the tentacle of a giant squid from Portugal Cove.

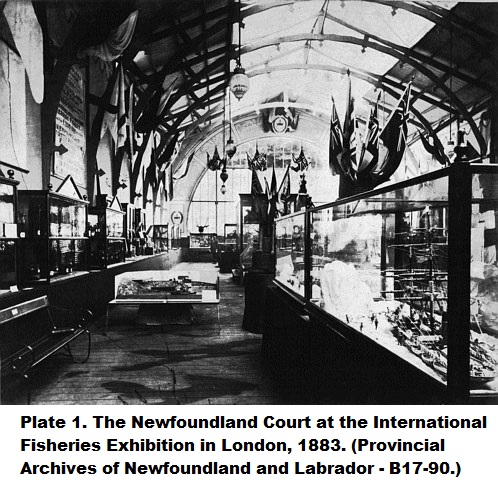

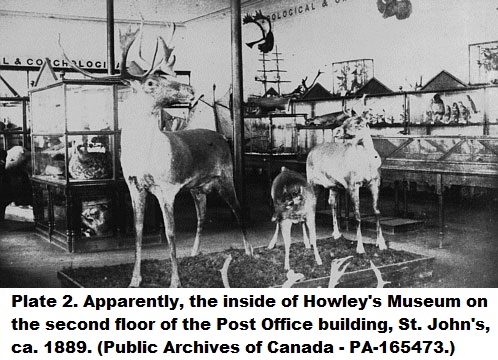

When Murray retired in 1883, Howley was appointed as both Head of the Geological Survey, and Curator of the Museum. One of his first tasks was to incorporate into the Museum - still at the Engineer's House [?] - the cases and many of the exhibits recently returned from the 1883 Fisheries Exhibition in London. Such two-way interchange of items between international exhibitions and museums had become common practice. With the completion of the Athenaeum Building on Duckworth Street, Howley moved both his office, and his museum into an "apartment" there. But space was cramped. After about four years, he removed the whole operation to the second floor of the new Post Office Building on Water Street. By 1887, St. John's had its first "real" public museum.

The collections grew ever more rapidly, and their variety increased. But, Howley soon found that running both a geological survey and a museum was a very daunting task. The priorities of the Survey almost always superseded those of the Museum, so the Museum was often neglected for months at a time. In addition, Howley continued to be plagued by the recurring demands of the "international exhibition". In 1889, he was required to find time to pull together exhibits for the show at Barcelona.

As luck would have it, the Great Fire of 1892 spared the Museum, in its west end location; but priorities and officialdom did not. The burned-out Customs Department was moved, temporarily, into the museum space. Exhibits had to be pushed out of the way, and the Museum was closed for a year.

In 1893, Howley and his assistant Albert Bayley, managed to refit the Museum, but the damage had been done; many of the natural history specimens had been ruined. Nonetheless, collections continued to accumulate, and the Museum carried on, as popular as ever.

In 1897, Howley was presented with a new challenge. The Government asked him to assemble exhibits promoting the resources of the Colony, to be sent to both the Imperial Institute in London, and the new Bureau of Museums in Philadelphia. The Imperial Institute had recently been set up to display the commercial products and resources of the Commonwealth Nations, and to act as a central agency for the promotion and facilitation of commercial enterprise. It was hoped that the Bureau in Philadelphia would perform a similar service to Newfoundland, in America.

For Howley, the preparation of these new exhibitions was a particular burden. Newfoundland's re-trenchment program, following the bank crash of 1894, had resulted in the curtailment of the Legislative grant to the Museum, as well as the cutting of Howley's salary, and the loss of one of his two assistants, Mr. Bayley. In 1897, Howley's other assistant, Mr. Thorburn, was lost to another government department, and Howley's salary was reduced still further by the "temporary" abolishment of the position of Museum Curator. But, Howley carried on alone. In addition to his work for the Survey and the Museum, he also continued to work on the two exhibits for overseas. In the end, though, he was not at all pleased with the meagre results achieved, especially with regard to the exhibits for the Imperial Institute. He continued to agitate, eventually successfully, for something better.

For Howley, the preparation of these new exhibitions was a particular burden. Newfoundland's re-trenchment program, following the bank crash of 1894, had resulted in the curtailment of the Legislative grant to the Museum, as well as the cutting of Howley's salary, and the loss of one of his two assistants, Mr. Bayley. In 1897, Howley's other assistant, Mr. Thorburn, was lost to another government department, and Howley's salary was reduced still further by the "temporary" abolishment of the position of Museum Curator. But, Howley carried on alone. In addition to his work for the Survey and the Museum, he also continued to work on the two exhibits for overseas. In the end, though, he was not at all pleased with the meagre results achieved, especially with regard to the exhibits for the Imperial Institute. He continued to agitate, eventually successfully, for something better.

By 1904, the Post Office had become increasingly anxious to evict the Museum from its building, in order to make space for a postal telegraph department. In response, the government debated closing the Museum and storing its contents. Howley made a number of passionate pleas on behalf of the Museum, suggesting that an extension to the Post Office might be the answer. Ultimately, the Museum was dismantled; though the exhibits remained in the Post Office building, stored in various places, including the attic. It seems that, despite events, the government had listened to the essence of Howley's case. In 1905, it began allocating surplus funds toward a new museum building. It also began negotiating for full ownership of the site that had been occupied by the Athenaeum before the Great Fire. In the meantime, Newfoundland was represented at both the Earl's Court and Franco-British exhibitions in London.

Construction of the new museum building was begun in 1907. As the structure neared completion, in 1909, the Post Office again began agitating to have the Museum's artifacts removed from its site. But, Howley stood firm, insisting that the exhibits would be ruined if the transfer was rushed. In 1910, yet another international exhibition effort was mounted - the Festival of Empire. But, the event was soon cancelled for a year because of the death of King Edward VII. This complicated matters surrounding Newfoundland's attempts at upgrading its exhibits at the Imperial Institute. The plan had been to transfer many of the exhibits directly from the Festival of Empire to the Imperial Institute. Howley was directly involved in all of these endeavours and travelled to London on at least two occasions. Concurrently, Howley was attempting to fit up his new museum building, and assemble its exhibits.

The new museum finally opened in 1911. From the beginning, the building was plagued with problems, including a balky steam-heating system, leaks in the roof sky-lights, and excessive sunlight falling on the exhibits. However, the museum exhibits were a great success, and the collections continued to grow. The Game and Inland Fisheries Board became great museum supporters in the area of natural history. They made it their policy to require scientific collectors from museums and universities abroad to deposit, in the Museum, certain specimens collected during their studies. But, Howley - the Museum's number one driving force - was nearing retirement. In 1915, at age 68, he published his renowned book on the Beothuk Indians. Thereafter, he seems to have faded from the scene. By 1917, letters concerning the state of the Museum building were being signed "William Duggan, Caretaker". Howley died on January 1, 1918. With him, an era passed; and the Museum slipped deep into the doldrums. The Year Book and Almanac of Newfoundland: 1922 listed the post of Director of the Geological Survey and Curator of the Museum as vacant; [May] O'Mara was Assistant Curator and Stenographer; William Duggan was Caretaker; and Harry F. Shortis was Historiographer. But the Museum remained open, and great things still occurred there occasionally.

One memorable event took place on the afternoon of June 3, 1922, when Governor Charles Alexander Harris, in an impressive military ceremony, presented the Museum with the recently re-discovered colours of the "Newfoundland Fencible Regiment". The years 1924-1925 saw Newfoundland participate in the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. The Museum appears to have shut down for a time in the late 1920s, since a reopening was announced for May 1928. During September of that year, the Museum received a visit from Mr. Harry Oberholser of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, largely for the purpose of examining and recording the Museum's many rare bird specimens. It was a significant visit, since all of the specimens examined were later destroyed by fire. The Museum was again closed to the public in October 1930, since sufficient public funds were unavailable to fix a number of leaks in the roof. In January 1934, the Hon. William Walsh, Minister Responsible for the Museum, found himself in hot water. He was arrested for allegedly stealing the Museum's valuable postage stamp collection, along with a number of mint coins and bank-notes. After a major trial, Walsh was released when a prima facie case could not be established against him. In March 1934, the new Commission of Government placed the Museum under the Commissioner of Public Utilities. Not long after, the institution was totally shut down, and its artifacts were variously dispersed and stored. The museum building was turned over to the Public Library, and the Department of Health and Welfare. It was a strange and schizophrenic time for the historic resources of Newfoundland. On the one hand, the Commission of Government closed the Museum, and dispersed its collections. On the other hand, it applied for a Carnegie Grant in support of the same institution. In August 1934, the Commission agreed that legislation should be drafted prohibiting the export of monuments and other historical relics from Newfoundland. But, without a doubt, the Commission of Government years, during the late 1930s and the 1940s, were the darkest in the Museum's long history. An unfortunate combination of factors, including incompetent storage arrangements, a disastrous fire, and outright disposal of artifacts, decimated the collections.

The minerals and fossils were originally taken to Memorial College and "dumped" there for the "use of the students". Most of the remaining natural history specimens were stored in the Fisheries Laboratory at Bay Bulls, where they were destroyed by fire on April 19, 1937. The historical and ethnological materials were variously stored in the cold-storage plant at Long Bridge, the Stott Building, the Brownrigg Building, Memorial College, and on the top floor of the Museum Building itself. Many of the specimens originally stored at Memorial College were later moved to the Old Laundry at the Sanatorium.

Ironically, by the end of October 1937, the Commission had agreed in principle to restore what was left of the Museum. But, before much could be done, the Second World War broke out, and everything was put on hold until peace was declared. Throughout the period, the Newfoundland Historical Society championed the Museum's cause. In 1946, responsibility for the Museum was transferred to the Department of Home Affairs. It was then decided that the Public Libraries Board would move to the lower floors of the Museum Building. The top floor would be used for a reconstructed Museum. Leo English was appointed Curator, but did not take up his duties in July of 1947. In May of 1947, it was agreed that legislation should be drawn up to govern archaeological discoveries. Mr. English - later with the assistance of Nimshi Crewe - began the task of rebuilding the Museum. Their work continued steadily, even as Newfoundland became a Canadian province in 1949. Mr. Adrian Digby of the British Museum was retained as a consultant. In 1955, "An Act respecting the Preservation of Historic Objects" assured the Museum's provincial status and support. The Museum finally re-opened in 1957. Upon Leo English's retirement in 1960, the Museum and the Archives were grouped together under the direction of historian and Chief Provincial Archivist Allan Fraser. The Museum itself continued to plod along much as before, but related projects began happening very rapidly. In 1963, the Naval and Military Museum opened under the curatorship of David Webber. In 1966, the Historic Markers programme began. In 1967, the first phase of the Newfoundland Museum's Gander Aviation Exhibit opened, and the restoration of the Quidi Vidi Battery was completed.

In 1968, a unified Historic Resources Division was created, and placed under the direction of David Webber. It comprised the Newfoundland Museum and Historic Sites sections. Allan Fraser directed the Archives Division as Provincial Archivist. In 1969, the Newfoundland Museum's Maritime Gallery opened at the St. John's Arts and Culture Centre. In 1970, Peter Dawson became Curator of the Newfoundland Museum. And, in 1971, the Museum tripled its space when the Gosling Library moved to new quarters.

In 1973, the "Historic Objects, Sites and Records Act" came into effect, and the Historic Resources Division, with Martin Bowe as Director, took on the additional responsibility of the Newfoundland Archives. That same year, a new federal government program began providing financial assistance to Canada's provincial museums. For the first time, the Newfoundland Museum was able to chart a course out of its Victorian mould. Work finally began to properly research and catalogue the collections. In 1976, the Museum again closed its doors; but this time it was for major reconstruction and renewal. Throughout the construction period, the small museum staff continued to fulfil its legislated mandate.

The latest version of that mandate - the "Historic Resources Act" (1985) - requires the Museum to: "(a) collect, catalogue, conserve, preserve, study and exhibit historic resources, ...; and (b) enlighten and educate the people ... respecting historic resources ...".

By the time the Newfoundland Museum re-opened in 1979, it had metamorphosed into a truly modern institution. Staff and facilities had increased, and there were curatorial areas in each of material history, archaeology/ethnology, and natural history. The Museum has continued to grow and progress, particularly in the areas of facilities, collections, and professional expertise. But it's still a struggle, Mr. Howley!