In Practice: Andrew Testa

In this interview, Mireille Eagan, Curator of Contemporary Art, speaks with Corner Brook-based artist Andrew Testa. Testa’s exhibition “slow time” is currently on display on Level 2.5 at The Rooms as part of the “Present Tense” series, which explores how artists are responding to the pandemic.

ME: Your previous work has often involved mindful attention to a place, and to aspects of everyday life that often go unnoticed. How did this body of work come about?

AT: This body of work was the result of the pandemic. I no longer had access to the Printshop at Grenfell, so my larger practice came to a halt. When I was home, I was anxious along with the rest of the world about what was going on, so I needed to occupy my time and work with my hands to keep my mind at ease. For some reason, I felt like I should be making useful things, so I started making clothes as well as wooden spoons from the wood of a felled tree.

My artistic practice is about mindful relationships, and I view my relationship with materials as cooperative. When making spoons, I work with how the wood wants to take form as opposed to my ideas of how it should be. In terms of the clothing, I have always learned how to mend my own clothing and making my own clothes was interesting to me. The outfits, as DIY camouflage, align with my own practice—to hide while also being visible. I wanted to blend into my environment, but I also wanted to become an odd character in the environment where people might feel perplexed but comfortable asking what I’m doing when I’m walking in the woods for my artistic practice. My clothing became an access point to talk with people about paying attention to the places that you’re in and the importance of listening.

During the pandemic, I became more aware of how my practice, my life and my teaching are not as easy to categorize and separate as I had once thought. Things are not just artworks or prints or a form of research—they are all intertwined. I stopped caring whether a walk was for artistic research or for the pleasure of just getting outside. That’s one of the reasons why I started making more useful things. It was seeing things as not just as an act, but a form of participation in the world around us and sharing that participation and thoughtfulness with others. It was also nice to make something that I could either use myself or send to my family back in Toronto and Kingston that they could utilize on a day-to-day basis. It was a way to connect and participate in lives that are more and more difficult to get close to.

ME: The exhibition does not show the finished items – the spoons and the clothing. Instead, it shows what most people would consider remnants like scraps of wood and fabric. Why is that?

AT: As a maker, I am very aware that I produce things and put them into the world, and that most of what is eventually shown in the gallery is the result of a long line of trials, failures and in-between cycles. I’m very process-oriented and I keep a lot of the off-cuts of what I make. Before the pandemic, for example, I kept my offcuts from my printmaking process, folding them and storing them. Eventually those folded prints became installations. For this body of work, it was a similar relationship where I would keep the offcuts of wood chips and fabric from clothing and come back to them at some other point.

By displaying the off-cuts, I am calling attention to the labour involved in creating a work. I want to share the in-between, the things that do not make it to becoming a spoon or an outfit or a piece of art in the capital “A” sense. It’s thinking about what it means to collaborate with materials such as a piece of wood or fabric, keeping and celebrating what is left behind. It is also about being aware of how much I produce, and the entirety of an object or a thing. The holistic part of a spoon includes everything I’ve left along the process. It’s about appreciating not only the result but the wholeness of something.

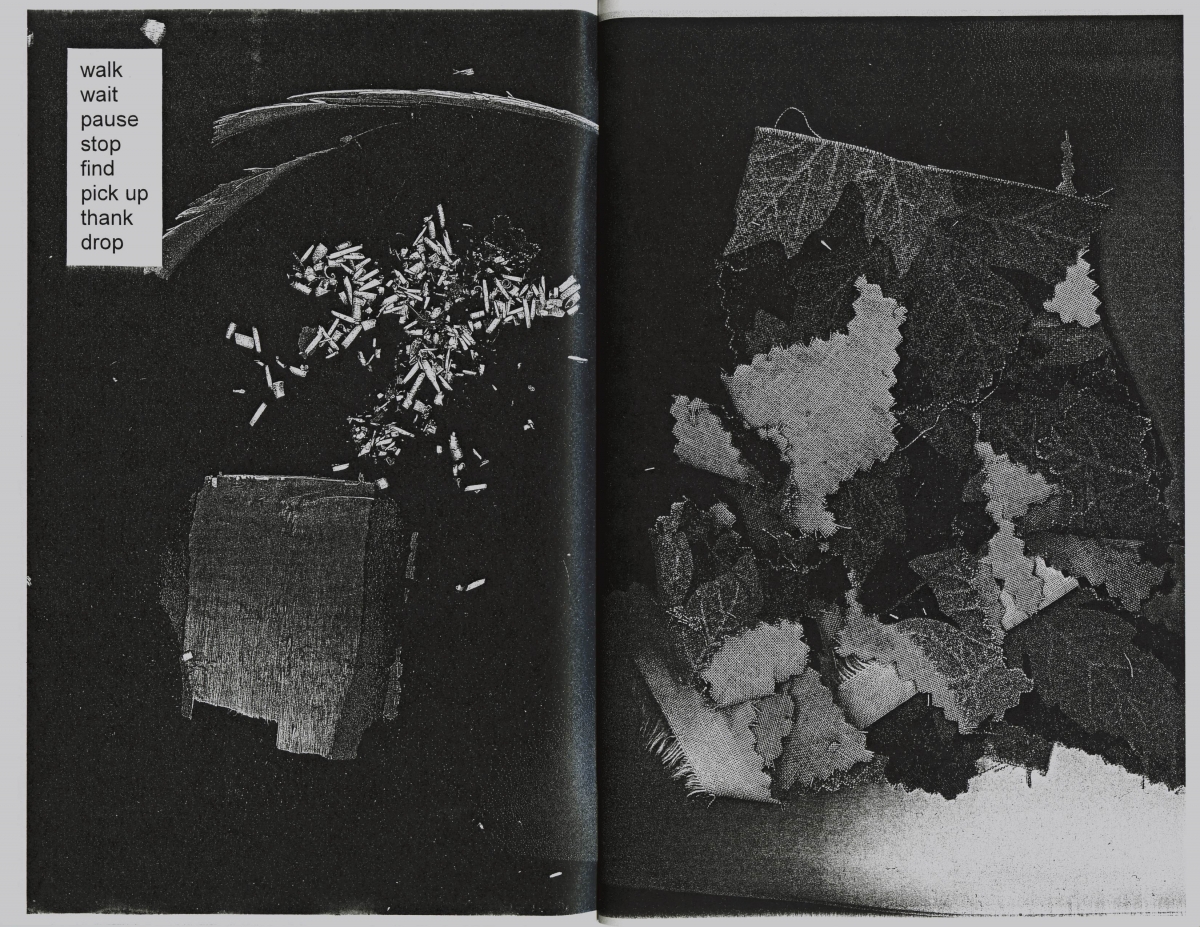

ME: Your artistic training is as a printmaker. Would you consider the zine you’ve made for the exhibition as a form of printmaking? Why translate the offcuts to a zine?

AT: It was a different way of looking at the off-cuts. It was scanning to see how else they can exist and be reflected upon. Photocopying is absolutely a form of printmaking. It is a duplication process that changes an original object from the initial form but while also being a copy—the same thing at the same time. In my zines, I scan the remnants and then created random patterns in the zine spreads by folding the resulting images together to see what new formal relationships can exist. So, as you look through the zine you will see these tiny collisions of content on different pages.

By creating the zine, I wanted to think about how artworks can be made more accessible and how to create conversations with viewers. Zines, for me, have always been accessible–they are not made from precious materials and in this exhibition, they are free to take.

Throughout the pages, there are lists. I often think in terms of words and lists, and including them becomes a point of access to start conversations—stopping, picking up, thanking, pausing, making a mistake. I hope that those words become a point of contact for conversation, whether that is between people or the other-than-human encounters we experience.

Image credits

Banner Image: Andrew Testa in the woods wearing his handmade clothing. Image courtesy of the artist.

Top Image: Wooden spoons by Andrew Testa. Image courtesy of the artist.

Middle Image: Installation view of “Andrew Testa: slow time” at The Rooms.

Bottom Image: Example of page from zine by Andrew Testa.