Newfoundland Samplers

Newfoundland Samplers

By Anne Chafe

Fall 1985

[Originally published in printed form]

This work in hand my friends may have,

When I am dead and layed in grave.

19th Century Sampler Verse

Samplers are among the few pieces of our material culture that were consciously designed, by women, to be preserved. These embroidered works, usually bearing the name of the needleworker, were proudly displayed in the family home. They were proof of the maker's proficiency with the needle and often functioned as a memorial after her death. The sentimentality associated with these decorative objects ensured their continued preservation and samplers worked during the nineteenth century have become cherished heirlooms.

A sampler is a piece of embroidered cloth composed of a combination of letters, numerals, motifs and verses worked in a variety of stitches. The word sampler is derived from the Latin word exemplum that describes anything that serves as a pattern for imitation or record. In early English literature the sampler was referred to by a variety of names such as exemplar, ensample, sampleth, sam-cloth and sawmpler. The original role of these needleworks was to serve as a sample of stitches, motifs and designs that could be referred to and copied in future sewing tasks.

A sampler is a piece of embroidered cloth composed of a combination of letters, numerals, motifs and verses worked in a variety of stitches. The word sampler is derived from the Latin word exemplum that describes anything that serves as a pattern for imitation or record. In early English literature the sampler was referred to by a variety of names such as exemplar, ensample, sampleth, sam-cloth and sawmpler. The original role of these needleworks was to serve as a sample of stitches, motifs and designs that could be referred to and copied in future sewing tasks.

In most parts of Canada, the history of sampler making has been extensively researched. In Newfoundland, however, samplers have remained neatly tucked away and preserved in blanket boxes, and only recently are they being recognized as valuable expressions of our past. A close examination of these needleworks can tell us a great deal about the women of Newfoundland during the nineteenth century. These embroidered pieces not only illustrate the integral part needlework played in their lives, but they are also indicative of the unique culture which determined the role of women at this time.

A piece containing the Ten Commandments surrounded by a decorative floral border is the earliest known sampler made in Newfoundland. It was completed by Amy Glynn of Burin on May 20, 1795. Undoubtedly, young girls were working samplers here long before this date. They were continuing a long standing tradition of their homelands, predominantly England and Ireland, from where most Newfoundland settlers migrated. Early samplers would have been modeled after European patterns, and Newfoundland pieces clearly exhibit traditional European designs and repertoire of stitches. Although Newfoundlanders were isolated from their motherlands, traditional patterns continued to be traded among friends or passed down through each succeeding generation and were repeatedly copied onto new works.

The sampler itself has chronicled changing needlework styles while gradually changing its own form. European samplers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were haphazardly embroidered by women of all social classes and tended to be long and narrow, a result of an accumulation of newly acquired patterns. In the eighteenth century, the style of samplers gradually changed as they began to take the form of a square or wide rectangle. At this time, they were used solely as experimental pieces for young girls between the ages of five to fifteen who were learning the art of needlework. Neatly worked rows of alphabets, numerals, motifs, and occasionally a verse, became the rule, so that by the beginning of the nineteenth century, samplers no longer served only as reference works. Instead, they were designed to be displayed and preserved as a certificate of the maker's dexterity.

Young girls took great pride in their work. As a testament to their deftness, many signed their finished pieces and often included their birthdate or the date on which their project was completed. Occasionally, the needleworker also stitched the name of her community onto her work: St. John's, Port de Grave, Greenspond, Twillingate, Grand Bank and Petit Fort are among the communities recorded on Newfoundland samplers. Due to the traditional nature of sampler designs and stitches, it is difficult to correctly attribute a sampler to a particular area of origin without such documented information.

Sewing was an integral part of a young girl's domestic education throughout the nineteenth century. During this period, the role of the woman in the home was glorified and, from a young age, a daughter was trained in the essential skills required for her future role as wife, mother and homemaker. Sewing was only one task in the diverse list of household chores. In Newfoundland, a woman living in the outports was an important complement to her husband. In addition to household duties and child rearing, she was expected to maintain a garden as well as helping her husband with the fishery. Given her heavy workload it is not surprising that a mother welcomed and expected any help a daughter could offer. At a very tender age, a young girl understood the validity of the couplet:

A poor man works from sun to sun

But a poor woman's work is never done.

As soon as she could manipulate a needle, a daughter was taught what would become a lifetime chore, and under her mother's direction, the impressionable child gradually became aware of society's expectations of her.

A typical household guide of the period, An American Frugal Housewife, written in 1836, expressed that "there is no subject so much connected with individual happiness and national prosperity as the education of daughters." Though not formal in nature, the execution of a sampler provided the ideal medium for such essential education. The task taught not only practical skills, but also reinforced the emotional and spiritual ideals a woman of the 1800s was expected to imitate.

A typical household guide of the period, An American Frugal Housewife, written in 1836, expressed that "there is no subject so much connected with individual happiness and national prosperity as the education of daughters." Though not formal in nature, the execution of a sampler provided the ideal medium for such essential education. The task taught not only practical skills, but also reinforced the emotional and spiritual ideals a woman of the 1800s was expected to imitate.

Sewing techniques were, of course, the most obvious and essential skills gained from working a sampler as each step in its creation involved a new proficiency that could be applied later to household chores. The textile used most often in the home was linen and this material appropriately served as a ground for samplers. To produce a sampler, a piece of linen was first cut, squared off and hemmed all the way round. This was a useful exercise in hemming and sewing straight seams. Next, a decorative border was usually embroidered along the sides. Such patterns could later adorn household items such as pillowcases, tablecloths and apron strings. When the border was completed, the child began to fill the remaining space at the top half of the ground with rows of alphabets and numerals. Although a variety of stitches, worked in either silk or woolen thread, are found on samplers, the universal stitch used was the cross stitch. The stitch was so common that by the end of the nineteenth century it was referred to as the sampler stitch.

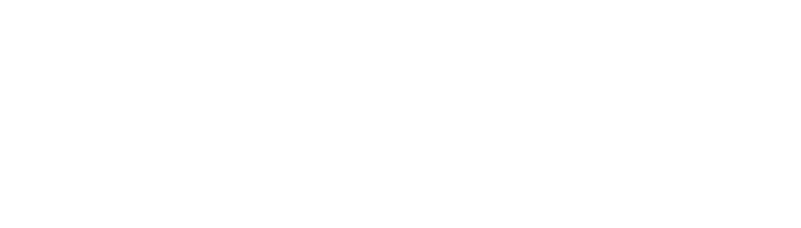

The making of clothing and other household items such as quilts and curtains was extremely difficult, expensive and time- consuming. Each step in producing an article had to be completed by hand. A family's linen was, therefore, a very valuable possession and, as such, was carefully marked, usually with the owner's initials. Articles such as underclothing and nightclothing were also numbered in the order of daily use. Such applications resulted in the term marking sampler which referred to a piece worked to acquire the skills needed for this necessary sewing task. In practising letters and numerals, the maker was also learning the basics of reading and writing as well as her own signature. Jane Walker's sampler (Plate 1), completed in 1800, is an example of such a practical exercise. Her sampler contains ten rows of meticulously stitched alphabets followed by two rows of random pairs of letters, possibly representing the initials of individual family members. Jane also practiced her numerals, squeezing them in on the right-hand side of her piece. The intricate decorative band, which Jane worked at the bottom, is a pattern that often adorned household linens of the period.

The design of the samplers required that all available space be utilized. Once the maker finished the prosaic task of practising her alphabet and numerals, she could then choose from a wide variety of designs to embellish her work. Biblical motifs were commonly chosen as part of a sampler's composition. Sampler making, therefore, was not only a means of obtaining essential domestic training, but their execution also served as a medium through which religious teachings could be instilled. The religious symbolism expressed in many motifs is ancient in origin.

In 1864, Amelia Moors adorned her sampler with such moralistic motifs. To the left of her signature was the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and to the right was the Tree of Life, which are discussed in Genesis 2:9-17. A basket of fruit above Amelia's name symbolized abundance and charity. A peacock above the Tree of Life signified the all-seeing eyes of God and the afterlife of Paradise, while a lion above the basket of fruit represented the resurrection. A crown signified hope and eternity, and crosses and diamonds represented Christ. Roses on Amelia's sampler were symbols of love, beauty, joy, silence and patience. Amelia's work attests to a religious upbringing. By working such motifs, the child was introduced to the religious ideology of her community.

Spiritual ideals were also expressed on samplers in the form of verses. Jane Walker included the religious message Remember Thy Creator in the Days of thy Youth (Ecclesiastics 12:1) on her work. The inclusion of a scriptural verse on an otherwise practical exercise suggests the important role religion played in the lives of our ancestors. Francis Daw, aged eleven, also included this universal verse on her sampler in 1837. However, she personalized her handiwork with a unique verse, composed specifically for her piece. It reads:

Twas in the barren isle of Newfoundland

In Port de Grave this sampler first was plann'd

Stitch'd by a clear unerring marking rule

At the Newfoundland public central School

Where the pure Word of God cannot lie

Is read to teach us to live and die

May I with friends and teachers number'd be

By Grace through Christ in God's great family

And through eternity that love adore

Which sav'd from woe a child call'd Fanny Daw.

This verse, obviously dictated by Fanny's teacher, vividly reflects the educational aim and religious ideologies of the Evangelical Newfoundland School Society that operated the school where Fanny stitched her sampler.

In sharp contrast to samplers produced under the direction of the Protestant faith, are those embroidered by Roman Catholic students instructed at the Presentation Convent in St. John's. Those of the Protestant persuasion tended to rely on the Scriptures as a source of inspiration, while Roman Catholics represented in their pieces the supernatural element of their religious beliefs. In comparison to other Canadian samplers, Newfoundland examples are unique in their religious expression. Inasmuch as tradition dictated the sampler's general composition, there was an opportunity for regional input. In Newfoundland, this occurred in the form of religious statements. The biblical references found on nineteenth century Newfoundland samplers reflect the religious climate of the island at this time.

In sharp contrast to samplers produced under the direction of the Protestant faith, are those embroidered by Roman Catholic students instructed at the Presentation Convent in St. John's. Those of the Protestant persuasion tended to rely on the Scriptures as a source of inspiration, while Roman Catholics represented in their pieces the supernatural element of their religious beliefs. In comparison to other Canadian samplers, Newfoundland examples are unique in their religious expression. Inasmuch as tradition dictated the sampler's general composition, there was an opportunity for regional input. In Newfoundland, this occurred in the form of religious statements. The biblical references found on nineteenth century Newfoundland samplers reflect the religious climate of the island at this time.

Throughout the nineteenth century, needlework instruction, which required the working of a sampler, was an important part of a young girl's education. It ranked in importance with reading, writing and arithmetic. Although Fanny's is the only known piece specifying that samplers were produced as part of a child's education, other examples of school work have survived. In 1857, Ann Winsor and Sarah Jane Whitmarsh, both fourteen years of age, embroidered remarkably similar works at a school operated by the Newfoundland School Society in Greenspond, Bonavista Bay. In each sampler the decorative border, alphabet script and verse are identical. Obviously, the teacher provided her students with a completed sampler that the girls, in turn, were required to copy onto their piece of linen.

In addition to the Society's schools, there were a variety of private schools established on the Island of Newfoundland, particularly between 1800-1850. Although most were located in St. John's, larger communities, such as Carbonear and Harbour Grace, boasted of such institutions. After 1807, The Royal Gazette frequently advertised these schools, and it is clear from the number of advertisements placed, that a great deal of competition occurred. The curriculum offered in these private schools was both practical and imaginative. In addition to the traditional academics, they taught such courses as bookkeeping, navigation, etching, music, history and geography. While this rounded education was designed for boys, the wife of the schoolmaster usually instructed young girls in needlework exercises. On October 29, 1812, Nathan Graham and his wife advertised in The Royal Gazette that they were opening a school in Maggotty Cove. Mr. Graham would teach reading, writing, English grammar and arithmetic while his wife would "instruct young Girls in plain and fancy Work."

In an earlier advertisement, which appeared on July 19, 1810, Mrs. Cleare informed the public that she was opening a school in St. John's, "to Teach young Ladies Reading and Spelling - Plain, Sampler and Ornamental Work." In distinguishing between these kinds of work, Mrs. Cleare acknowledged the existence of two forms of needlework, plain and fancy. Plain sewing referred to the necessary forms of household needlework. Fancywork included all the non-utilitarian forms and was undertaken by affluent women who had considerable leisure time. Although a sampler was considered an exercise in plain sewing, it was not uncommon for examples of fancywork to find their way into the sampler's composition.

The ideals that nineteenth century women cherished were often expressed in sampler verses. Virtue, selflessness, humility, industry, and contentment were traits that the Victorian woman was expected to exhibit. Rachel's first verse is an ode to modesty:

Modesty makes large amends for the pain it gives

the person who labour under it by the prejudice it

affords every worthy person in their favour.

Warnings against looming evils were also featured in sampler verses, as were statements concerning death, such as the one quoted above. Such gloomy thoughts are understandable, given the high mortality rate and primitive medical care of the nineteenth century. Death was ever present during this period, and children were not sheltered from the harsh realities of life.

Despite a rather stereotyped composition, samplers did allow for considerable individual experimentation, both in stitches and design. The possibilities were endless, and depended on the maker's particular tastes and contemporary styles. A variation in sampler form appears to have occurred in Newfoundland during the 1840s. Young needleworkers began to incorporate family histories into their samplers by giving the birth and death dates of various family members. With the inclusion of a pious verse, these family record samplers could easily become memorial pieces. A sampler worked by an unknown needleworker, circa 1864, records the birth and death dates of the Forward family of Grand Bank. The maker expressed her grief in the form of a verse:

See gentle patience

smile on pain See lingering

hope revive again.

Hope ruines the tear from

sorrows eye And faith

points upwards to the sky.

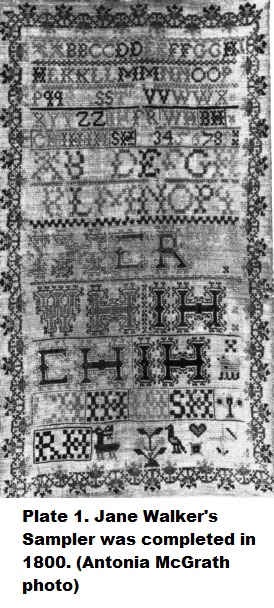

By the middle of the century, such outward signs of mourning began to be applied to a new type of needlework called memorials, which were worked solely to commemorate the death of a loved one. These works became popular towards the end of the 1800s, a time when it was in vogue for women to display life's cruelties in their handiwork. Through memorials, women could openly express their grief. Many record quite tragic events, such as the Mercer memorial(Plate 2). In this particular example, a mother tried to rationalize the death of her six infant children.

Although memorials are distinctly different from samplers, several elements of the sampler's composition, such as the decorative border and the cross stitch, were incorporated into these pieces. Yet, it was the popularity of perforated paper, which served as the ground for memorials, which eventually led to the universal decline of the art of sampler making. This paper, which was available in Newfoundland by at least 1851, had pre-punctured uniform holes that made it easier to work and to obtain neat stitches. The paper, or Bristol board, as it was originally called, required less time, concentration and skill. Women could then afford to spend time doing other needlework projects. Another type of needlework that became popular towards the end of the nineteenth century were mottoes. These consisted of sentimental sayings that were commercially produced as kits with the pattern preprinted on the perforated paper and brightly coloured wool included. Popular mottoes, such as God Bless our Home (Plate 3), Home Sweet Home, What is Home Without a Father and There is no Place Like Home, all emphasized the importance of the family's home in daily life.

espite the popularity of these new forms of needlework, girls continued to produce samplers until the end of the nineteenth century. Pieces worked during the latter half of the 1800s tended to be much smaller and more simply designed than earlier examples. As late as 1893, Angela Hann of Petit Fort, Placentia Bay demonstrated her needlework abilities on a piece of loosely-woven linen. Such exercises had become merely a formality by this time, and samplers executed during this period do not demonstrate the prowess or creativity of earlier needleworkers.

At the turn of the twentieth century, needlework continued to be taught in Newfoundland schools. However, the girls began to collect their sewing samples, such as gathering, buttonholing, making tucks and attaching tapes, in blank exercise books designed to display the students' level of achievement. During the 1930s, there was a renewed interest in sampler making in the home. It was initiated by numerous magazines and books published on the subject. Yet, in this decade, sewing instruction was introduced only to children in primary grades as a preliminary to a regular course in Household Arts taken in higher grades. This course prepared the student in the social science of housekeeping and homemaking, the forerunner of the Home Economics course.

In the 1990s, samplers are again in vogue. Magazines advertise their quaintness and craft stores promote their charm. Today, sampler making is undertaken by choice, as a hobby by women with considerable leisure time. No longer a compulsory part of a young girl's domestic, social and religious education, samplers are reminders of a way of life experienced by Newfoundland women.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING:

Chafe, Anne. The Religious Content in Newfoundland Samplers. Newfoundland Quarterly XXX (Winter 1985), 42-48.

Fawdry, Marguerite, and Deborah Brown. The Book of Samplers. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1980.

Maitland, Leslie. While Thus My Fingers O'er the Canvas Move. Canadian Collector 17 (January/February,1982), 46-49.

Wults Fox, Hyla. Samplers. Canadian Antiques and Art Review, 11, 111 (August/September, 1981), 46-55.