Furniture Making in Newfoundland: A General View

Furniture Making in Newfoundland: A General View

By Walter Peddle

Summer, 1981

Revised Fall, 1991

[Originally published in printed form]

Until the late 19th century, full-time furniture making specialists were a rarity in outport Newfoundland. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries and for most of the 19th, the permanent population of the region, for the most part, remained too small too support such relatively unessential tradesmen. Newfoundlanders were pluralistic in occupation by necessity. Fishermen, for example, also hunted seals, cut lumber and built boats. They occasionally worked as sailors, carpenters, stone masons or blacksmiths. Similarly, in the slack periods of their specialized employment, such tradesmen as joiners, blacksmiths, coopers, wheelwrights and shoemakers went fishing, sealing or sailing. Sometimes they also pursued the specialized work of another trade. For example, a cooper might build furniture; a sail maker, make fish casks. Consequently, Newfoundland outport furniture, in the majority of instances, was either homemade or crafted by part-time furniture makers whose skills were most often acquired through traditional transmission rather than through the serving of a formal apprenticeship.

One major consequence of the absence of furniture making specialists is that outport Newfoundland did not develop a regional school of furniture design which would have provided guidelines for furniture making based on the common needs and tastes of the fishing-oriented residents. Lacking the uniformity of design that such guidelines would have insured, Newfoundland outport furniture, nevertheless, shares some similar characteristics. These include the kinds of materials used, the wide range of skills exhibited in construction, the large repertoire of models on which designs are based, the high instances of one-of-a-kind pieces, and the synthesis of design elements that normally are not found in other vernacular and high style furniture making traditions.

One major consequence of the absence of furniture making specialists is that outport Newfoundland did not develop a regional school of furniture design which would have provided guidelines for furniture making based on the common needs and tastes of the fishing-oriented residents. Lacking the uniformity of design that such guidelines would have insured, Newfoundland outport furniture, nevertheless, shares some similar characteristics. These include the kinds of materials used, the wide range of skills exhibited in construction, the large repertoire of models on which designs are based, the high instances of one-of-a-kind pieces, and the synthesis of design elements that normally are not found in other vernacular and high style furniture making traditions.

The earliest surviving pieces of Newfoundland outport furniture reported date from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The more skilfully crafted of these survivors are made from local woods, chiefly pine and birch, and in many instances show almost pure transmission from any one of a number of British regional furniture making traditions, including those of English West Country, Ireland and Scotland. Chests of drawers and kitchen dressers of both English West Country and Irish design, for example, have been found throughout outport Newfoundland, while a significantly large number of simple side chairs of the Scottish type have been discovered, especially in Conception Bay North in communities such as Harbour Grace and Upper Island Cove. This furniture exhibiting design transmission from the source areas of the early Newfoundland settlers, almost certainly was made by British tradesmen such as shipwrights, house builders and joiners and their apprentices who were recruited by the major English- Newfoundland merchant firms to construct their residences, offices, fishing premises, ocean going vessels, schooners and fishing boats. Such highly skilled woodworkers could not then be found amongst the small Newfoundland born population. Presumably, during the slack periods of their employment, these British tradesmen built selected items of furniture for the homes of the more prosperous Newfoundland residents. Other early surviving pieces of Newfoundland outport furniture display widely varying degrees of skill and, presumably, were homemade by the residents for their own use.

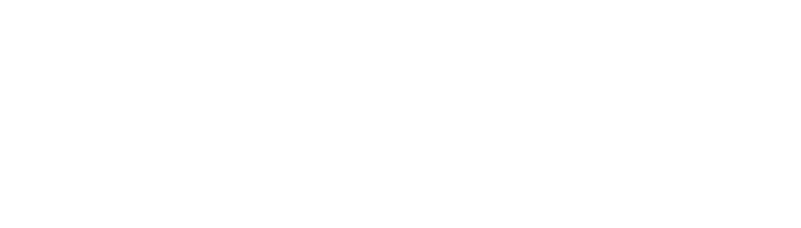

One early piece of Newfoundland furniture that shows nearly pure transmission from West Country furniture design is a painted pine kitchen dresser (Plate 1) which is on exhibit at the Hiscock House in Trinity, Trinity Bay. Like West Country examples, the rack is made separately from the free standing base. In fact, the rack of this example is removable. Unlike West Country dressers, however, the rack has no back boards. The dresser is finished in two contrasting colours: the rack, blue; the base, red. The porcelain knobs appear to be replacements. It was found in Trinity East, Trinity Bay and was probably made early in the nineteenth century. Several very similar dressers have also been discovered in that area and it is likely that they were all built by the same craftsman.

While this dresser displays strong West Country influence, a dresser (Plate 2) on exhibit at the Newfoundland Museum, Duckworth Street, St. John's, shows pronounced elements of Irish influence. Like Irish kitchen dressers, this example has continuous sides to the rack and base. Dressers made in other parts of Britain had racks built separately from the base. Furthermore, the unusual shallowness of the dresser suggests the Irish custom of utilizing wall space rather than floor space - a practice reflecting the lack of floor space in single-storey nineteenth century Irish cottages. The centre drawer of this painted pine dresser is a fake and the drawer pull once attached to it is missing. Because it was originally constructed as an integral part of a house, the dresser has no back. It is painted in contrasting colours of blue and white, except for the bracket base which is painted orange presumably to match the baseboard of the house into which it was first built. The dresser was found in Keels, Bonavista Bay and was made circa 1800.

While this dresser displays strong West Country influence, a dresser (Plate 2) on exhibit at the Newfoundland Museum, Duckworth Street, St. John's, shows pronounced elements of Irish influence. Like Irish kitchen dressers, this example has continuous sides to the rack and base. Dressers made in other parts of Britain had racks built separately from the base. Furthermore, the unusual shallowness of the dresser suggests the Irish custom of utilizing wall space rather than floor space - a practice reflecting the lack of floor space in single-storey nineteenth century Irish cottages. The centre drawer of this painted pine dresser is a fake and the drawer pull once attached to it is missing. Because it was originally constructed as an integral part of a house, the dresser has no back. It is painted in contrasting colours of blue and white, except for the bracket base which is painted orange presumably to match the baseboard of the house into which it was first built. The dresser was found in Keels, Bonavista Bay and was made circa 1800.

The majority of surviving pieces of Newfoundland outport furniture date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some of this furniture was produced in factories operating in Harbour Grace and in several other of the more populated outport communities, or was constructed by full-time or part-time furniture makers. A significant portion of it, however, was homemade by outport residents for their own personal use. Interestingly, it is often very difficult to distinguish between commercially made and homemade outport furniture. Both were crafted from local woods and reclaimed lumber, especially packing case material, by craftsmen having widely varying degrees of knowledge about furniture construction and design, and experience in constructing furniture.

In the absence of a regional code of furniture design, Newfoundland outport furniture makers normally patterned their pieces after models seen and being used in their home communities. Models included items made by other Newfoundland furniture makers, furniture crafted by earlier British tradesmen, and handmade and mass-produced furniture imported from various sources, both in Great Britain and in North America generally. Some models were faithfully copied. In many instances, however, elements of several different furniture models - often unrelated in their design and use - were combined, perhaps to achieve a more suitable piece of furniture for a special context or need. Occasionally, elements of either domestic or institutional architecture were also synthesized with furniture design in an attempt to have the newly constructed item conform with the special character of the household or community. Such syntheses sometimes resulted in rather bizarre- looking pieces of furniture.

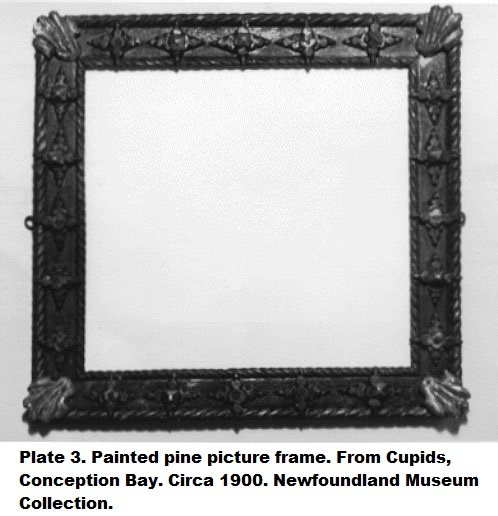

The practice of incorporating familiar ideas in the design of newly constructed pieces of furniture resulted in the retention of numerous elements of design and decoration strategies earlier introduced from various British regional furniture making traditions. Such echoes from Newfoundland's immigrant roots can be found even in the latest examples of Newfoundland outport furniture made after the turn if the 20th century. One such example is a painted pine picture frame (Plate 3) found in Cupids, Conception Bay. The applied chip-carved crosses are reminiscent of a form of decoration called "tramp art" which was practised in many areas of North America from about 1860 until 1920. The applied rope twist and shell carvings, however, link this interesting object to Ireland. The rope twist motif is commonly found on buildings in Irish coastal towns, as well as on pieces of Irish furniture. Shell carvings were used by Irish carpenters as decorations, both on shop fronts and on furniture. The picture frame was made circa 1900.

Examples of the work of the earliest cabinet makers have yet to be reported. These craftsmen began arriving from Great Britain by the late eighteenth century to set up shop in the largest and most rapidly developing settlements, such as St. John's and Harbour Grace. By this time, West Country merchants had opened offices in Newfoundland. The resulting import and export trade caused many local communities to flourish and created conditions favourable for cabinet making enterprises. One of the earliest cabinet makers was John Dialy. We know of him because he - "John Daily, cabinet maker and joiner" - leased a house in St. John's in 1789 from "Thomas Stokes, Merchant of Devon, England" and the dated lease is preserved in the Provincial Archives.

Examples of the work of the earliest cabinet makers have yet to be reported. These craftsmen began arriving from Great Britain by the late eighteenth century to set up shop in the largest and most rapidly developing settlements, such as St. John's and Harbour Grace. By this time, West Country merchants had opened offices in Newfoundland. The resulting import and export trade caused many local communities to flourish and created conditions favourable for cabinet making enterprises. One of the earliest cabinet makers was John Dialy. We know of him because he - "John Daily, cabinet maker and joiner" - leased a house in St. John's in 1789 from "Thomas Stokes, Merchant of Devon, England" and the dated lease is preserved in the Provincial Archives.

Advertisements appearing in local newspapers after the turn of the nineteenth century indicate that the early cabinet makers had broad experience and built furniture similar to the fashionable products that were being crafted from imported woods such as mahogany, back in Great Britain. One cabinet maker, George W. Hancock, for example, who opened a cabinet and upholstery business in St. John's in 1815, advertised in the Newfoundland Gazette of that year that he had previous experience in his craft in London, Bath, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Dublin and Cork. Another cabinet maker, James Johnston, advertised in the Mercantile Journal in 1816 that he carried mahogany dining, breakfast and card tables and chairs and had on hand a large stock of seasoned wood of all kinds.

While no examples of the work of the earliest cabinet makers have been reported, a mahogany occasional table (plate 4) made by a relatively early craftsman has been found. It bears a label identifying it as a product of Samuel Creed who set up shop in St. John's around 1835. Creed, a British trained cabinet maker, had worked for some time at his craft in Halifax, Nova Scotia before moving to St. John's.

While no examples of the work of the earliest cabinet makers have been reported, a mahogany occasional table (plate 4) made by a relatively early craftsman has been found. It bears a label identifying it as a product of Samuel Creed who set up shop in St. John's around 1835. Creed, a British trained cabinet maker, had worked for some time at his craft in Halifax, Nova Scotia before moving to St. John's.

The early cabinet makers must have been few in number. Hutchinson's Newfoundland Directory for 1864 lists only seven in St. John's: Thomas Bearns, Thomas Cole, William Daymond, Michael Dunne, Richard Goff, Patrick Hagerty and William Pickerd. In Harbour Grace John Mitchell was the only cabinet maker listed.

It is believed that Pope's was Newfoundland's first and longest surviving furniture factory. This firm began making a small amount of furniture and coffins in 1860 and later expanded to mass-produce a general line of household furniture including mattresses and bolsters. Pope's Furniture Factory ceased operation in 1958. According to the Census of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1884, there were four furniture factories in St. John's East employing 77 persons altogether and three in St. John's West employing 14 persons. The Directory of St. John's, Harbour Grace, Carbonear, 1885-6, however, credits St. John's with just three factories but identifies only two: Bearns Furniture Factory, Springdale Street and Newfoundland Furniture Factory, Forest Road.

The Newfoundland Furniture Factory made furniture comparable to the better grades of furniture manufactured in factories on the North American mainland and in Great Britain as one bedroom dresser (plate 5) attests. The dresser is made from walnut and has a marble top. Construction details such as the hand cut dovetail joints in the drawers indicate competent and careful workmanship. A label on the back of this imposing item reads: "Newfoundland Furniture & Moulding Co. Show Rooms - Duckworth Street Steam Factory - Forest Road". The date, Sept. 1887, is written on the underside of the marble top.

By the turn of the twentieth century there were more than a dozen furniture making businesses operating in the more populated areas of Newfoundland. These included cabinet making/upholstery enterprises and factories employing form only one to a dozen or more men. The furniture they produced ranged widely from expensive high quality items crafted from fine imported woods to cheap mass-produced goods improvised from locally available materials.

By the turn of the twentieth century there were more than a dozen furniture making businesses operating in the more populated areas of Newfoundland. These included cabinet making/upholstery enterprises and factories employing form only one to a dozen or more men. The furniture they produced ranged widely from expensive high quality items crafted from fine imported woods to cheap mass-produced goods improvised from locally available materials.

Furniture factories reached their peak activity early in the twentieth century but then began to decline. Their diminution may reflect increased competition from factories on the North American mainland. The dropping of tariffs on Canadian furniture after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949 undoubtedly contributed to their ultimate demise. Cabinet making and upholstering shops which may have offered more highly priced custom made cabinetwares presumably began to decline much earlier due to the steadily increasing competition from local and mainland factories. Cabinet making shops had at least one advantage over the larger factories, however. When competition for new furniture was great, unlike a large factory, a small cabinet making and upholstering business might survive doing repair work, refinishing and re-upholstering.