Conception Bay Furniture Maker

Conception Bay Furniture Maker

By Walter W. Peddle

Fall 1982

Reprint Fall 1991

[Originally published in printed form]

Dog power was one of the things that helped Henry William Winter's furniture making business to be a success.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, Henry William Winter, an ambitious self-taught furniture maker in Clarke's Beach, Conception Bay, mass-produced furniture using simple hand tools and a few primitive machines. These included a foot-powered jig saw, a foot-operated lathe and a larger lathe designed to be driven manually or powered by a dog.

At the time, rural Newfoundlanders had little cash to spend on furniture. In fact, pieces were often homemade. For those who did have money, there were sources other than Henry William Winter from which to choose. Furniture was also commercially produced in a few of the larger nearby outport communities such as Harbour Grace and Bay Roberts and in relatively large factories in St. John's. As well, pieces could be ordered through mail order catalogues from sources both in Newfoundland and other areas of North America. Yet, despite the poor state of the local economy and considerable competition, for about half a century Henry William Winter sold his furniture over a wide area in rural Newfoundland.

Surprisingly, considering its size, most of the information about Henry William Winter's furniture business has been gleaned from a very few family members and friends.

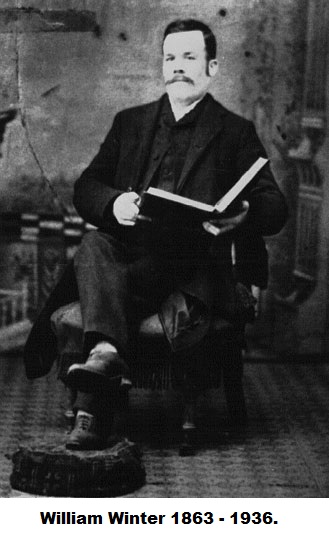

Nothing in the way of ledgers or personal records was found, and Winter ran no business ads in the local newspaper, The Bay Roberts Guardian. Only two published references relating to his furniture-making business were discovered. One was in the 1921 census of Newfoundland which listed Henry William Winter as a cabinet maker. The other was in his obituary in The Daily News, St. John's, Newfoundland, June 19, 1936: "Mr. Winter was a cabinet maker by trade and owned and successfully operated a furniture business in Clarke's Beach and had made extensive business connections with most parts of the country."

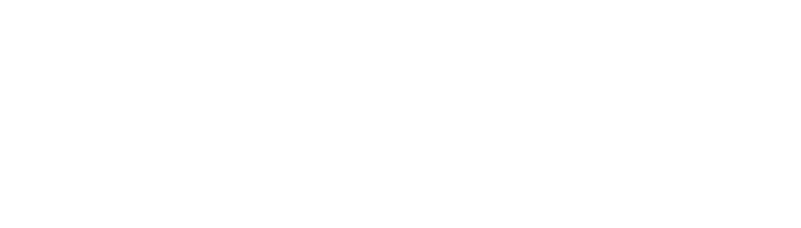

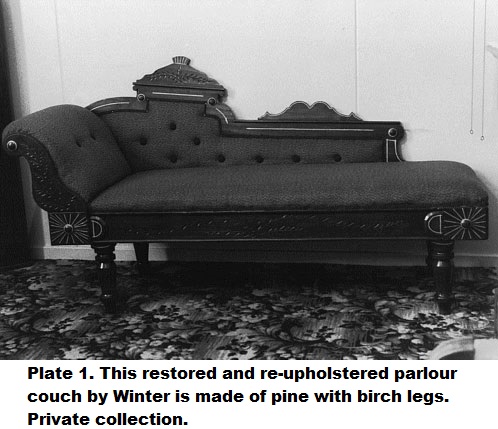

Fortunately, a reasonable number of Henry William Winter's pieces have survived and have been identified. The examples shown here, although accompanied by relatively scanty information, should provide some insight into the personality of this remarkable, energetic man and his thriving business.

Fortunately, a reasonable number of Henry William Winter's pieces have survived and have been identified. The examples shown here, although accompanied by relatively scanty information, should provide some insight into the personality of this remarkable, energetic man and his thriving business.

According to the baptismal records of the Roman Catholic Basilica in St. John's, Henry William Winter was born to John Winter and Helen Hayes in that town in 1865. The St. John's directory of that year lists a John Winter, cooper, living at 95 New Gower. The earliest family recollections of Henry William Winter are of his attending the Methodist school in Clarke's Beach at age seven or eight (there was then no Roman Catholic school in the area). It is also remembered that Helen ran a general store in Clarke's Beach at that time. However, there is no family recollection of John. It is likely he may have died in St. John's shortly after Henry William's birth. The family may have then moved to Clarke's Beach to live near relatives.

Before the 1940s in outport Newfoundland, it was the usual practice for young people to leave school at an early age to pursue a livelihood. It is believed that Henry William left school at about age twelve to help his mother run her general store. Supplies for the store were delivered by schooner. In Clarke's Beach, the water was too shallow for such large vessels to dock close to shore, and supplies were ferried from the schooner in small fishing boats called trap-skiffs. For this purpose Henry William, at age 14, built a trap-skiff that could hold fifty barrels of flour. Family sources say that this was the first indication of his ingenuity and manual dexterity.

It is not known when Henry William Winter began his furniture making business. Family sources say that he first received training as a wheelwright from a relative, Tom Smart, but found this business to be unprofitable. Often a fishermen would come for his wheels and would not have the money to pay for them. Knowing that the wheels were necessary for the man to continue earning his living, Henry William would let him have them, hoping that payment would be made at a later date. Often, payment was never received. Family sources reasoned that Henry William turned to furniture making because only those having the money to pay for it would approach him to buy furniture.

It is not known when Henry William Winter began his furniture making business. Family sources say that he first received training as a wheelwright from a relative, Tom Smart, but found this business to be unprofitable. Often a fishermen would come for his wheels and would not have the money to pay for them. Knowing that the wheels were necessary for the man to continue earning his living, Henry William would let him have them, hoping that payment would be made at a later date. Often, payment was never received. Family sources reasoned that Henry William turned to furniture making because only those having the money to pay for it would approach him to buy furniture.

It is reasonable to assume that Henry William Winter began his furniture-making business before the turn of this century. One of his sons, William (born 1905) and William's wife Florence still live in the old family home in Clarke's Beach. William's earliest recollections go back to around 1911 and he claims his father was making furniture at that time. A neighbour, Cyril Richards, who was born in 1894, has memories of Henry William making furniture around 1901.

Henry William's original workshop was located on the main highway across the road from his house. This building was pulled down around 1921 and a new two-storey building measuring approximately 42 feet by 18 feet was built on the same location. The first floor of the new building was used mostly as a paint shop, the second floor, for furniture making. The two wood-working lathes, however, were located on the first floor. As a sign of trade, a kitchen chair was placed in a prominent position at the front of the roof, overlooking the road and the bay. Though this building has not been standing since about 1969, many people in Conception Bay still have vivid memories of it, perhaps because of the many unusual stories circulated about the chair. William Winter commented on this: "The chair was on the roof, you know as a sign of furniture, sure. They made everything out to it. Probably the ghost chair and, you know, (some) said that the chair was up there ready for someone, waiting for someone that was drowned to come back, and all this old stuff."

William Winter has boyhood memories of helping his father in the workshop. He particularly recalls the unpleasant task of sandpapering the furniture and, with the help of his brother, powering the large lathe which was then located in the original building. The boys would rotate a large drum by means of two cranktype handles, one on each side at the centre. The drum was approximately eight feet high and six feet deep and had a heavy band of iron applied around the outside to provide momentum for the turning. William remembers his father telling him of the unusual manner in which the drum was rotated before he and his brother were big enough to assist with this work. A large dog would run on wooden steps around the inside of the drum like a hamster in its rotary cage, thus providing the power to operate the lathe. The dog eventually died, however, and Henry William was unsuccessful in training another dog to perform the chore.

William Winter has boyhood memories of helping his father in the workshop. He particularly recalls the unpleasant task of sandpapering the furniture and, with the help of his brother, powering the large lathe which was then located in the original building. The boys would rotate a large drum by means of two cranktype handles, one on each side at the centre. The drum was approximately eight feet high and six feet deep and had a heavy band of iron applied around the outside to provide momentum for the turning. William remembers his father telling him of the unusual manner in which the drum was rotated before he and his brother were big enough to assist with this work. A large dog would run on wooden steps around the inside of the drum like a hamster in its rotary cage, thus providing the power to operate the lathe. The dog eventually died, however, and Henry William was unsuccessful in training another dog to perform the chore.

According to William, his father obtained locally most of the lumber he required for his business. He cut his own pine - it grew plentifully nearby - and purchased a great quantity of lumber, particularly fir, from local mills. William commented: "See, he'd go to a mill say, Bay Roberts or down to Bishops, or somewhere and he'd know all the lengths he needed and if it was say forty-five dollars a thousand (feet) well he'd give them an extra five dollars and (they'd) let him pick the wood he wanted and the length he wanted, you know." In the early 20th century, Henry William made use of the packing crates in which commercial goods were shipped. Though the pine, spruce, and fir boards that comprised these crates were usually of poor quality, they were suitable for the backs of case furniture and for parts normally hidden from sight. No doubt he obtained most of this material from his wife who, like his mother in earlier days, operated a general store.

William recalls that the workshop was a very busy place and that his father did a lot of other things besides making furniture. He also made sulkies (light two-wheeled carriages) and sleighs and the necessary harnesses for them. He painted and repaired carriages; made picture frames from imported lengths of moulding; fashioned church pulpits, made caskets and, using his hearse, performed some of the services of an undertaker. William remembers that his father's busiest time, however, was in the summer and fall when he built the furniture. During the summer he made and stock-piled parts and during the fall the furniture was assembled. "You'd go out today and there'd be nothing out there. But when he started to pull it all together, if you went out there that day you couldn't get in. Everything was a piece of furniture! But all that before that was just stacked up, you know, a thousand pieces of one and five hundred of another". William believes that his father worked alone and did not employ any help. Cyril Richards, on the other hand, recalls a Matthew Fowler working under the supervision of Henry William during the busiest months.

According to William, his father's general line consisted of bedroom sets (a bureau and a washstand), parlour sets (a settee, two side chairs and a table), parlour sideboards, couches, panelled beds, rocking chairs, kitchen drop-leaf tables, lamp tables, kitchen washstands and mantel pieces. Judging by the identified examples that have been discovered to date, bedroom sets and parlour sideboards were Henry William's best sellers by far. William also remembers that his father imported unassembled wooden chairs (probably from Dominion Chair Company Limited in Bass River, Nova Scotia), fitted the parts together and sold them for 75 cents each. In addition to his general line, Henry William received many special requests for furniture. A comment made by William suggests that these requests challenged his father: "He would often stay awake most of the night building it in his mind."

According to William, his father's general line consisted of bedroom sets (a bureau and a washstand), parlour sets (a settee, two side chairs and a table), parlour sideboards, couches, panelled beds, rocking chairs, kitchen drop-leaf tables, lamp tables, kitchen washstands and mantel pieces. Judging by the identified examples that have been discovered to date, bedroom sets and parlour sideboards were Henry William's best sellers by far. William also remembers that his father imported unassembled wooden chairs (probably from Dominion Chair Company Limited in Bass River, Nova Scotia), fitted the parts together and sold them for 75 cents each. In addition to his general line, Henry William received many special requests for furniture. A comment made by William suggests that these requests challenged his father: "He would often stay awake most of the night building it in his mind."

William recalls that his father usually gave the bedroom pieces two coats of yellow paint followed by a light or a dark oak water stain, applied with a brush and then worked with rollers and combs to create a fake-grained finish. While examination of his surviving work confirms this, examples have been discovered on which a clear shellac or lacquer finish was applied over a dark stain.

Generally, Henry William's furniture reflects styles that are earlier than those currently popular in his day. Though construction short cuts were common for mass production, it is interesting that much of his furniture was generously embellished, revealing his penchant for ornamentation.

William partly attributes the popularity of his father's furniture to the fact that it was priced very cheaply. He remembers that around 1912, his father's bedroom sets sold for fifteen dollars, parlour sets forty dollars, parlour couches twelve dollars, kitchen couches seven dollars and mantelpieces, eight dollars and up. Henry William's prices must have been attractive and his production prolific, because he sold not only a large quantity of furniture locally through his own shop but also supplied on a regular basis, two general dealers elsewhere. One was Charles Cohen of Bell Island, the other, Batten Brothers of Humbermouth near Corner Brook. According to Cyril Richards, a brother-in-law of Sam, Mark and Don Batten, the furniture would be picked up at Clarke's Beach by schooner and brought to Humbermouth. Some of it, however, was exchanged by Batten Brothers with fishermen at coastal settlements, particularly in Notre Dame Bay, for lumber and for fish.

William partly attributes the popularity of his father's furniture to the fact that it was priced very cheaply. He remembers that around 1912, his father's bedroom sets sold for fifteen dollars, parlour sets forty dollars, parlour couches twelve dollars, kitchen couches seven dollars and mantelpieces, eight dollars and up. Henry William's prices must have been attractive and his production prolific, because he sold not only a large quantity of furniture locally through his own shop but also supplied on a regular basis, two general dealers elsewhere. One was Charles Cohen of Bell Island, the other, Batten Brothers of Humbermouth near Corner Brook. According to Cyril Richards, a brother-in-law of Sam, Mark and Don Batten, the furniture would be picked up at Clarke's Beach by schooner and brought to Humbermouth. Some of it, however, was exchanged by Batten Brothers with fishermen at coastal settlements, particularly in Notre Dame Bay, for lumber and for fish.

Talented craftspeople like Henry William Winter are often overlooked because of the standards that are used to evaluate their products. Unfortunately, few people give consideration to the fact that such craftspeople worked to their own standards which were determined partly by local tradition and partly by the uniqueness of their situation. In any event, Henry William's furniture is interesting and significant not simply for its beauty or for the quality of its workmanship, but for what it reveals about his ingenuity and the statement it makes about an earlier era in Newfoundland.