Helloland! Notes from the Curators

A series by Darryn Doull and Melony Ward

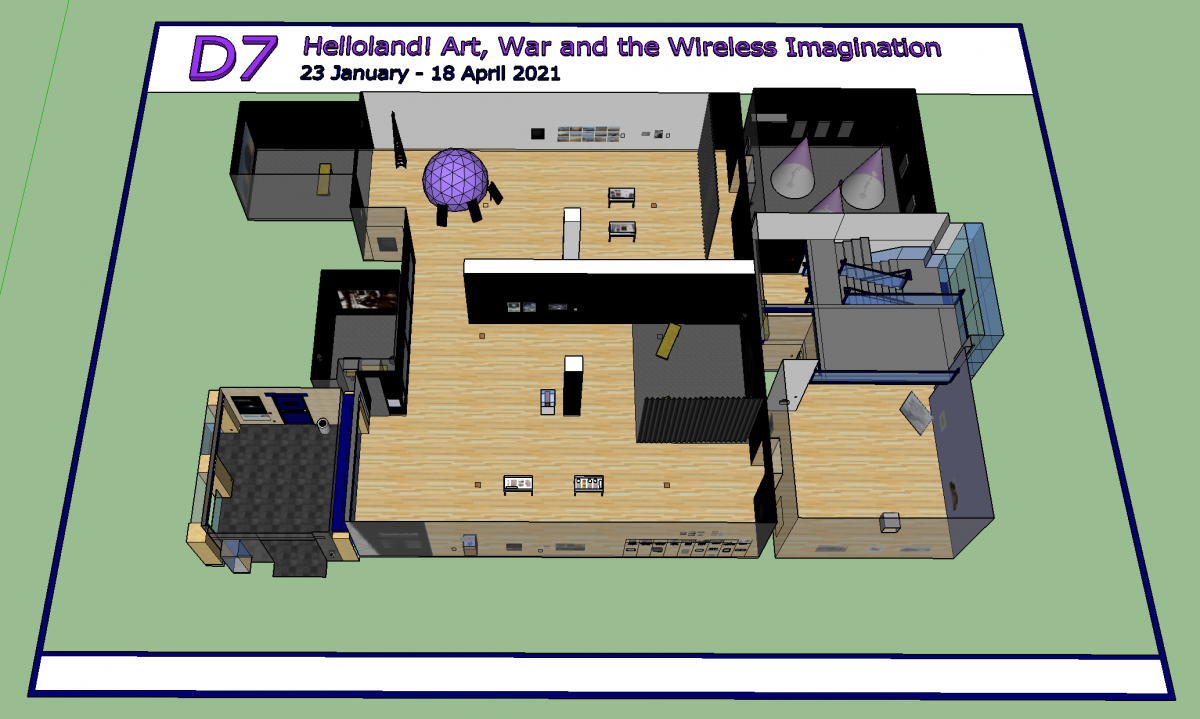

This page is home to a series of notes from the curators of Helloland! Art, War and the Wireless Imagination. These notes bring together fragments of curatorial research, historical context and information about featured artists and their work. Collectively, the blog will tell many of the stories that live within the exhibition and it will evolve in much the same order.

One artist from the exhibition will be highlighted each week. Each artist will be ‘paired’ with museological objects, archival images and/or historical documents that share a common theme. In some cases, resources for further reading will also be provided.

New posts will be added every Wednesday until April 21, 2021.

Image credit: Installation view, Helloland! Art, War and the Wireless Imagination. Photo by m + e photography.

April 21

Christopher Pratt

Memorialization and Remembrance

For the fifteenth and final regular post of this weekly series, we focus on memorialization and remembrance. In the February 17 post (The Power of Form, A Form of Power), we invited readers to think about radio and to try to identify the form that an idea of radio took. Radio, broadly speaking, was framed as something with both form and function. It was transitory and provisional, immaterial and physical. When reflecting on the idea of radio, one was likely drawing upon memories of listening to, operating and/or looking at a radio. It was a reflection on memory.

Memory is emotional and is never a perfect impression of reality. Memories are affected by the ways in which information is stored, retrieved, corrupted or otherwise associated with other senses and events. Each step, year or increment away from the original event tends to bend a memory further from the truth. Of course, all of this data loss does not make memorialization unimportant. Remembering is essential for us all (globally speaking) to move forward, to avoid the same mistakes we have made before and to magnify our successes and discoveries. While giving form to these larger memories can take myriad forms, two of the most common are representations in art (including visual artwork, literature and more) and in physical icons like coins, tokens or public monuments.

Renowned Newfoundland painter and printmaker Christopher Pratt has been documenting his life and the locations around him since the 1950s. His images are located somewhere between fact and fiction. Each work is infused with memories of significant people and places, and tempered by his aesthetic interests in a refined simplicity and innate order. Speaking about the origins of his work in November 2004, Pratt said:

“I think that it’s fair for me to say that my work is essentially autobiographical and I say that because I’ve never really been preoccupied with the history of art or art about art and my work essentially comes from my environment but you have to take a very broad view of the term environment. It’s not just obviously my geographical environment although that’s very important it’s also the social environment, the family environment of my childhood, memories that go back to there…and experiences that followed. It’s also the environment of things that I have read and encountered subsequently. But the bottom line really is that my work is the response to my life.” [1]

For these two works (one a preparatory sketch for the other), Pratt reflects on the military histories of Naval Station Argentia (1941-1994). By the end of the Second World War, the fishing villages of Argentia and Marquise, NL, were transformed into a massive American naval air station and army base. The area’s 750 residents (and three cemeteries) were relocated. The Commission of Government provided relocation compensation of $3,000 to $6,000 for land that had been in families for generations.

Fully operational by December 1941, the base was home to the largest American task force in the Atlantic. In addition to anti-submarine and anti-aircraft surveillance services, the Atlantic Weather and Ice Patrols were also stationed in Argentia. The change could not have been more significant for the small communities. Small fishing vessels were replaced by the world’s largest military ships and recovered U-boats.

By 1943, more than 12,000 American military personnel were stationed at the 3,900 acre Argentia base. After the war, the base continued to be used for monitoring foreign naval vessels. The last American forces withdrew in 1994, formally handing over the facilities to the province. In these works, Pratt documents a skeletal monument of an historic military base through precise depictions of a former radio room. This quiet memorial to an important history centres around a former hub of wireless communications. If these ruins could speak, one can only imagine the stories it could tell and the memories it would hold.

The archival object for this week memorializes another aspect of the same history. The Victory Nickel was produced by the Royal Canadian Mint amidst some of Canada’s darkest days. The young country was shocked by the massive losses of life in the Dieppe Raid (August 1942) and the Battle of the Atlantic throughout the Second World War. Between dwindling morale at home and the steadfast belief that the war could still be won, the Mint produced this coin for circulation.

The coin, designed by engraver Thomas Shingles, was partly inspired by Sir Winston Churchill’s iconic V for Victory sign, giving the nickel its name. These nickels were produced between 1943-1946. The bold design was replaced with the comparatively quaint beaver that we are familiar with today after the war. There are two other interesting aspects of the coin. The first is that they are not actually made of nickel. Due to the war effort, nickel supplies were needed for armour plating or weaponry and could not be spared in the quantities required to produce these coins (millions were minted each year). Instead, the coins were produced using a bronze alloy. The second interesting thing is that these coins actually contain a coded message. Along the rim of each coin, the patriotic message “We win when we work willingly” is included using Morse Code, placing the wireless imagination of Helloland! into the pockets of many Canadians.

By brush and by bronze, these objects memorialize aspects of the Second World War. The former is extremely localized, alluding to the military histories of Argentia and the international cooperation of Newfoundland and the United States during the war effort. The latter is national and captures Canada’s irreplaceable contributions to a global conflict that changed the world. Both of these physical impressions help articulate memory and facilitate remembrance with iconic design and aesthetic resolution.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Christopher Pratt (left to right): Study for Argentia: Monument to the American Presence (With Friends Like That), 2005, graphite on paper; American Monument: Radio Room, Argentia, c.1999, 2005, oil on paper mounted to board. The Emily Christina Dawe Collection, Gift of Christopher Pratt, The Rooms. Photo by m + e photography.

Middle 1: United States Navy, U.S. Naval Station, Agentia, NL, during the Second World War, c. 1945. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NAS_Argentia_aerial_view_c1945.jpg Accessed March 27, 2021.

Middle 2: Canada Mint, Victory Nickel, 1945, bronze alloy. Designed and engraved by T.H. Paget and Thomas Shingles. Collection of Melony Ward.

Bottom: Installation view, Helloland! Art, War and the Wireless Imagination. Photo by The Rooms.

Sources:

(1) Christopher Pratt, Artist Page on the National Gallery of Canada website. https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artist/christopher-pratt. Accessed March 31, 2021.

April 14

Andrew Wright

Survey and Surveil

The energy behind a wireless imagination (the invisible signals reverberating through the air) all run aground and wash ashore somewhere. The spectral waves of electromagnetic radiation are embedded in metal in the end: in receivers, microprocessors and cables. Connections can be drawn between the reception of wireless signals on an antenna and wavelengths of light impressing upon celluloid film inside a camera, or, to be more technologically present, onto an image sensor.

Any exhibition about wireless imaginations will likely become grounded at some point. In her introduction to Northrop Frye’s The Bush Garden, Lisa Moore states:

Frye poses a terrifying conundrum: the refusal of the Canadian landscape to be fettered or framed or coaxed into submission by perspective or cliché. We cannot hide in a garrison from “out there.” The best we can do, Frye suggests, is look; but perhaps we need to squint. … We hold the terror of the unknown at bay long enough to make art of it. [1]

Andrew Wright is often squinting at the land. His conceptually informed work is made in a range of media, though he is best known for his photography and often uses it in decidedly non-traditional ways. He is not one to simply make a pretty picture or document a place: that would be a compromise, an omission, a fault. Instead, his landscapes offer contexts for viewers to explore the edges of perception and understanding, in matters of concrete reality and emotional depth.

Thinking about Wright’s 2012 work, Nox Borealis, Celina Jeffery identifies that Wright “does not seek the picturesque as there is something uncertain and dystopic even in his personal subversion of being on top of the world, which results in images that are far from comfortable and familiar… There is something remote and incalculable about this place, this other side of the world which most of us will never access, but which is as crucial to our panoramic sense of self.” [2] Although it considers another work, the quote is still productive when thinking about APEX: Interloper.

APEX: Interloper consists of seventeen photographs that form a panoramic shot of Apex, Nunavut (63⁰43’28.5”N, 68⁰27’00.6”W). In Helloland!, three images from the series mark a transition in the exhibition between communal aspects of radio broadcast toward the implementation of radar technologies. The environment of Apex is surveyed, revealing a natural beauty and subtle incursions of colonial ambition.

The images resist an all-encompassing view. On one hand, the work is not fully present(ed); we have only an excerpt of a view to begin with (three of the seventeen photographs are included in the exhibition). The position within the exhibition is similarly dislocated. As the work straddles two large rooms, there are few places for a viewer to stand back to gain a full, unencumbered view of the photographs. The same limitations in scope and scale that constrain the series in most display contexts also affect the viewer here. When standing before the photographs, our bodies mirror the artist's own when he captured the images and confront a landscape that refuses “to be fettered or framed or coaxed into submission.” [3]

Looking more closely at the image on the left, an array of large storage containers come into focus in the background. Their white bodies are barely discernible from the rest of the environment. An informed observer might recognize a trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company along the frozen shoreline of the image on the right. Across all three images, there is a blanket of ice and snow draped upon ancient rock and water. We remember that global warming threatens the balance of this beautiful landscape.

Finally, peaking just above the horizon line of the third image is a series of radomes (below). The infrastructure is a subtle nod to the area’s military history. Before reverting to its original Inuktitut name, Iqaluit, in 1987, the area was known as Frobisher Bay. As Frobisher Bay, it was home to a major United States air base. The establishment of this base drew the Hudson’s Bay Company post from Ward Inlet to the area in 1943 in order to take advantage of the improved transportation and communications services. The growing settlement eventually became a center for DEW Line construction operations, bringing tons of supplies and many people into the area. [4] Later, Iqaluit became an official communications center for the Eastern Arctic and today is the location for one of twelve Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS) hubs across Canada. The Iqaluit MCTS “performs Alert and Warning Network (AWN) desk duties and provides Navigational Warning services.” [5]

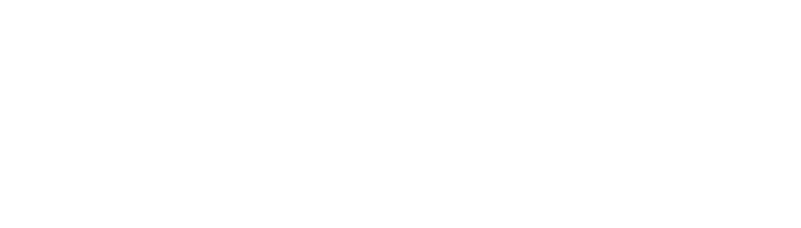

Picking up on this thread of navigation, we turn our attention toward two information cards about the Battle of the Beams. Based on the book by RV Jones, and printed in Italy for the Imperial War Museum (London, UK) in 1977, these cards are part of a larger series including titles like “The Jet Engine,” “The Special Squadrons” and “Submarine Tracking Room.” The Battle of the Beams refers to an early period of the Second World War when German forces were night bombing the United Kingdom. The ‘beams’ refer to a locational aid using radio waves that helped bombers navigate to their targets with great accuracy.

This technology had previously been used on a smaller scale to help a plane land. In short, two ‘beams’ of radio waves (representing left and right) were sent into the air. By flying a plane into these signals, receivers on board could determine if they were flying in one beam or the other (too far left or right). The beams were designed so that a plane positioned directly in the middle of the two beams could navigate to the given location, like an airstrip.

The Germans learned how to do this at a much larger scale, guiding planes with incredible accuracy to far-flung factories and specific targets under the cover of darkness. The British figured out what was happening and began sending their own signals to confuse the incoming planes. The Germans were convinced that the British were somehow bending or distorting their signals, as opposed to sending their own. After briefly introducing a new system based on similar principals (one that was immediately countered by the British), the Germans abandoned the use of this type of navigation over the UK.

This post began with a survey of land, and ended with a surveillance of air. And of course, nothing is so simple and tidy. There are deviations, exclamations and confusions anywhere that a wireless imagination might take us. Perhaps, as a means of conclusion, it is worthwhile to circle back to Northrup Frye, by substituting each appearance of the word ‘literature’ with ‘art’ in this quote from The Educated Imagination:

The [artist] is neither a watcher nor a dreamer. [Art] does not reflect life, but doesn’t escape or withdraw from life either: it swallows it. And the imagination won’t stop until it’s swallowed everything. No matter what direction we start off in, the signposts of [art] always keep pointing the same way, to a world where nothing is outside the human imagination… [Art] is not a religion, and it doesn’t address itself to belief. But if we shut the vision of it completely out of our minds, or insist on its being limited in various ways, something goes dead inside us, perhaps the one thing that it’s really important to keep alive. [6]

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Andrew Wright, Apex: Interloper (excerpt), 2020, chromogenic prints on aluminum composite board. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by m + e photography.

Middle: Installation view, Andrew Wright, Apex: Interloper (excerpt), 2020, chromogenic prints on aluminum composite board. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by m + e photography.

Bottom: Information cards, The Secret War: Battle of the Beams I + II, 1977. Produced for the Imperial War Museum, London, UK. Collection of Melony Ward. Photo by The Rooms, edited by Darryn Doull.

Sources:

(1) Northrup Frye. The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination. Toronto: Anansi, 1971, Introduction.

(2) Celina Jeffery, “Beyond Nature,” Preternatural. Brooklyn: Punctum Books, 2011, p. 16. Download a copy of the text for free here: https://punctumbooks.com/titles/preternatural/

(3) Frye, The Bush Garden, Introduction.

(4) Iqaluit city history from municipal website, via the Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20141211185403/http://www.city.iqaluit.nu.ca/i18n/english/history.html. Accessed March 25, 2021.

(5) Canadian Coast Guard, Marine Communications and Traffic Services program information. Website. https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/mcts-sctm/program-info-programme-eng.html. Accessed March 25, 2021.

(6) Northrup Frye. “Giants in Time,” The Educated Imagination and Other Writings on Critical Theory, 1933-1962. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006 (originally published 1963), p. 465.

April 7

Alan Collier

Listening in Labrador

The focus for this week takes us to Labrador. While much has been made of the wireless connections on the island of Newfoundland (most notably, Marconi’s first trans-Atlantic message in 1901), Labradorians were also early adopters of wireless communications. In the beginning, a common application was for communicating with nearby ships at sea and in the harbours. The technology was also used for entertainment and, as we shall soon see, the betterment of health care services in the region.

One of my first steps when beginning the research process for a new exhibition is to be as familiar with the pertinent collection(s) as possible. I use the database and conduct searches by artist, date, medium, donor and/or by key words in the titles. These basic searches will identify some initial leads. Another step in the process is to physically view objects in the collection storage vault whenever possible. Exhibition records and images of artworks are great first steps, but standing in front of the object is an entirely different relationship. Information and documentation is something that you engage with, while a strong work of art can also reach out to you.

While going through the vault for Helloland!, a small painting by Alan Collier caught my eye. According to the database, the date is unknown, so it would not have come up in my searches. The title is also lacking any specific clues about what has been painted, short of a geographic location and where it was painted from: Cartwright, Labrador, Sketched from the M.V. Nonia. Useful context, but nothing that immediately established a relevant thematic connection. As I looked over the small panel (a simple, confident and serene composition) three beacon lights shone out from the right side of the image. The three tall masts are part of a wireless telecommunications system still visible in aerial images of Cartwright today (though the shoreline has somewhat changed from what Collier saw).

In his article “An Ontario Artist of Newfoundland and Labrador,” published by Newfoundland Studies in 2013, Peter Neary notes that Collier had visited Newfoundland in 1969.[1] This particular trip included a three week trip along the Labrador coast aboard the MV Nonia. Leaving on July 20, Collier took over 600 photographs and made several recordings of Inuit speech on a tape recorder. Upon his return, Collier met Peter Bell, then curator of Memorial University’s art gallery and an important leader in the burgeoning provincial art scene. An exhibition was organized for the following year, opening in September, 1970. Ten works in the exhibition were purchased. Three of these were for the Memorial University Art Collection, including Cartwright, Labrador, Sketched from the M.V. Nonia.

One last connection of interest: Cartwright was home to the Pinetree Line radar station N-27. The site was closed in 1968. A new, minimally-attended long range radar installation was installed in 1998 as part of the North Warning System.

To further build on this story of wireless telecommunications and radio in Labrador, we borrowed a fantastic image of Aggoek Pitseolak from the Canadian Museum of History (above). The image was taken by photographer, artist and historian, Peter Pitseolak. Peter was born in 1902 in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut. His first recorded photo was taken in the 1940s, and he went on to document a period of great change in Inuit life. He stated that the setup of his photos was with an eye to the future. This photograph shows his wife Aggeok, tuning their radio. Aggeok was an active collaborator with Pitseolak, and became an accomplished developer and printer of her own photography. One of his many cameras is visible beneath the radio set. While both the Pitseolak and Collier images date from the mid-1900s, they are a part of the story of the early adaptation and use of wireless communications in Labrador and across the Arctic during the preceding years.

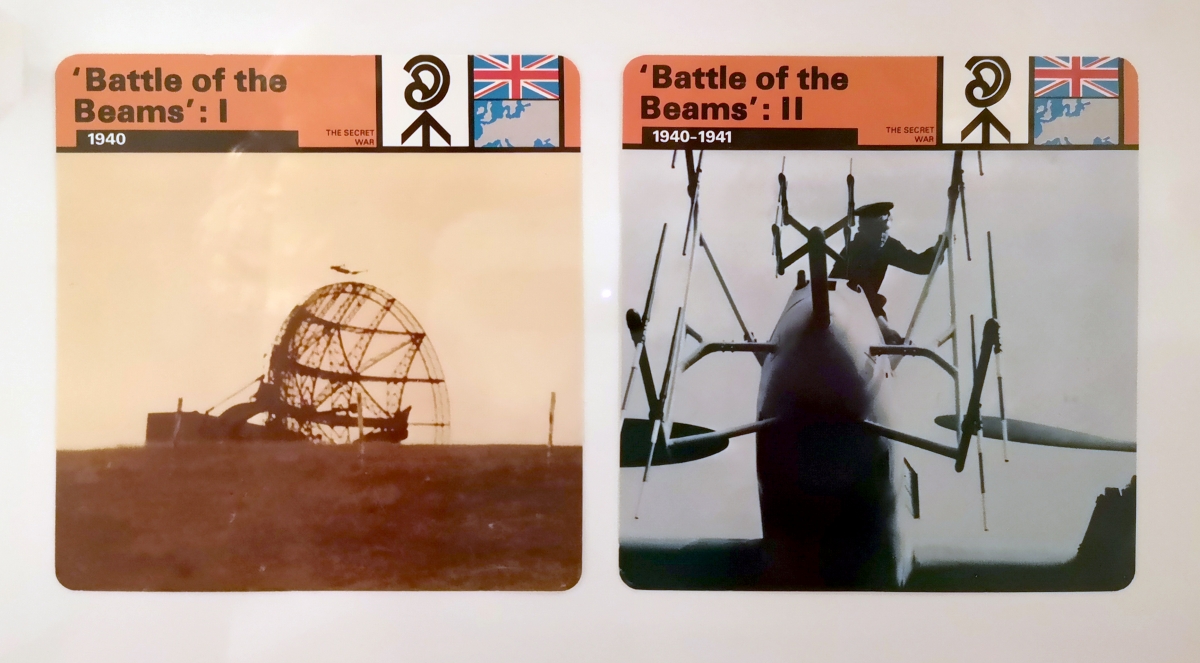

The archival component for the week is a two-page letter written by Dr. Wilfred Grenfell. It was typed aboard the SS Strathcona (you can read about the 1942 demise of this ship in last week’s post) on a letterhead from the International Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen on August 16, 1909. In it, Grenfell lobbies the Colonial Secretary of Newfoundland to support the “Wireless Telegraph System on the Labrador Coast,” writing:

...I want to represent to you that I have placed a wireless installation on the Mission boat “Strathcona” and that, lying at our wharf in the harbor at St. Anthony, I can with my ordinary storage cells easily speak to Belle Isle and hear what Belle Isle is saying to passing ships. May I venture to bring before the Government the claim of St. Anthony as the most important place now on the French Shore for the wireless station instead of Groais Islands?...

...It would be of incalculable advantage to the rapidly increasing number of residents, to the new Company mining at Goose Cove, and to the hundreds of schooners that both spring and fall take advantage of the admirable harbor of St. Anthony on their way to and from the fishery.

I would like also to call the attention of the Government to the fact that the Canadian Government have so far recognized the value of our hospital at Harrington being placed in better communication, that they have gone to the expense of moving their wireless station from Whittle Rock - fourteen miles distant - to re-erect it near the hospital...

While Grenfell clearly had a number of personal interests that would benefit from a closer proximity to wireless communications infrastructure, he also points to the broader impact that the technology would have on the region. It contributed to the fishing and mining industries, made the waters safer, and had advantages for the health care services that could be provided at the hospital in Harrington. Of course, it shouldn’t be ignored that this narrative also played some part in the colonization of the North (“... the claim of St. Anthony as the most important place now on the French Shore…”).

Together, these stories rightly acknowledge Labrador as being an important location in the early days of wireless communications and the wireless imagination that would come to change the world.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, left to right: Alan Collier, Cartwright, Labrador, Sketched from the M.V. Nonia, date unknown, oil on board. Memorial University of Newfoundland Collection, The Rooms; Peter Pitseolak, Aggeoak Pitseolak adjusting the radio, 1940-60, digital reproduction. Canadian Museum of History, 2000-182. Photo by m + e photography.

Middle 1: Alan Collier, Cartwright, Labrador, Sketched from the M.V. Nonia (detail), date unknown, oil on board. Memorial University of Newfoundland Collection, The Rooms.

Middle 2: Peter Pitseolak, Aggeoak Pitseolak adjusting the radio, 1940-60, digital reproduction. Canadian Museum of History, 2000-182.

Bottom: Installation view, Letter from Dr. Wilfred Grenfell to Colonial Secretary of Newfoundland, August 16, 1909, ink on paper. The Rooms. Photo by m + e photography.

Sources:

(1) Peter Neary, “Alan Caswell Collier: An Ontario Artist of Newfoundland and Labrador,” Newfoundland Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2, Fall 2013, p. 266-292.

March 31

David Blackwood

Disaster at Sea

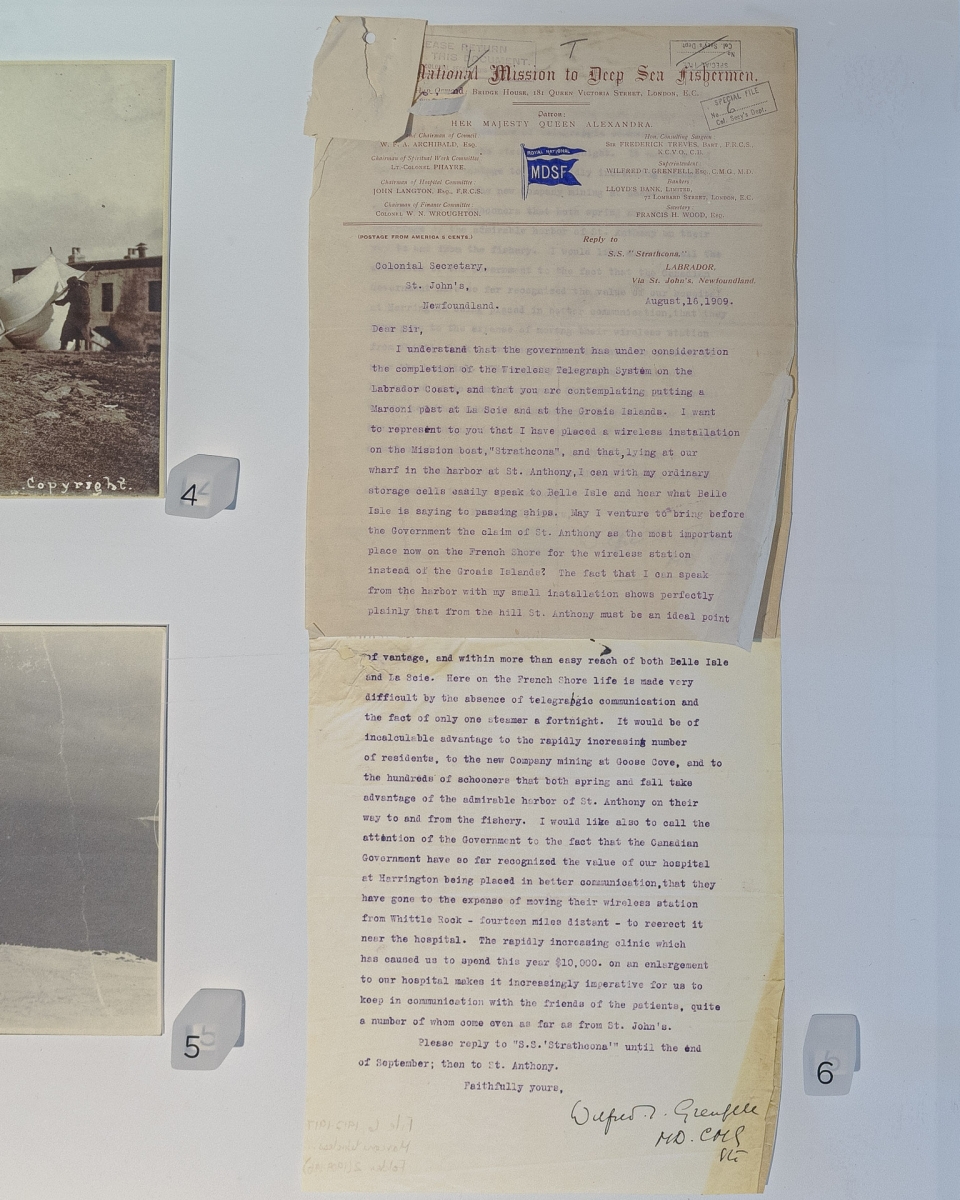

This week, we consider two maritime disasters with great historical significance to the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. In the first, we look back at the tragedy of the SS Newfoundland through the eyes of David Blackwood and his powerful series titled The Lost Party. In the second, a recovered artifact from the SS Rose Castle stands as a testament to Bell Island’s role in the Second World War. Wireless communications equipment is the thread uniting both stories.

Exactly 107 years ago today, one of the great tragedies of the province's maritime history was unfolding in the North Atlantic. 132 sealers of the SS Newfoundland (below) had become stranded on ice fields in quickly deteriorating weather. Despite being the most hazardous local fishery in the early 1900s, sealing brought fishermen back every season with the opportunity for generous pay. The treacherous task required sealers to leave the safety of their vessels and travel by foot - over many kilometers and for hours at a time - across unpredictable ice floes in search of their harvest. Landing the coveted pelts of the semiaquatic mammals was dangerous and difficult work.

Between March 30 and April 2, 1914, blizzard conditions, lack of shelter, limited provisions and inadequate equipment collectively led to the death of 77 men on the ice. Numerous survivors lost limbs to frostbite back on land. The full story involves another ship, the SS Stephano, captained by Abram Kean, and mutual confusion about where the sealers were located during the storm (Heritage: Newfoundland & Labrador has a more detailed account of the events here). A confounding factor of the situation was a lack of wireless communications equipment. The owners of the SS Newfoundland had failed to view wireless radio as a safety device. Instead, they had removed the equipment when it had failed to produce a larger haul during previous years. In this case, they were not able to confirm that the sealers had reached the safety of the other ship, or to confirm that they were indeed stranded on the ice.

Ultimately, the presence of wireless communications equipment might not have avoided the disaster entirely. Had it been present, however, it may have enabled a rescue mission to commence much sooner and contribute to a less tragic result. In the aftermath of this event, and a similar disaster for the SS Southern Cross, the government passed legislation in 1915 mandating all sealing ships to utilize wireless equipment, among other provisions.

One of Canada’s most widely recognized and celebrated printmakers, David Blackwood, reflected on this tragic story in a series of prints titled The Lost Party. Produced through the 1960s and early 1970s, the series consisted of 50 etchings. The stark, powerful images invite viewers to gaze upon the stricken sealers amidst the harrowing storm, as they fought against wind, sea and ice to make it home again. In these works, the sense of scale shifts from intimate moments to grand sweeping vistas, and moments of personal clarity wrestle with mass hallucination.

Blackwood’s decision to use an aquatint etching process of intaglio printmaking is effective for his subject matter. The technique, developed sometime between 1650 and 1750, combines the crisp lines of intaglio printing with a broad range of tonality from the aquatint process. The exact technique includes selectively covering a metal plate (traditionally copper or zinc) with powdered rosin. This is typically done with a rosin box or by hand. The rosin settles on the plate (like dust settling evenly across a bookshelf) and hardens onto the metal surface with the controlled application of heat. The entire metal plate is then submerged into a bath of acid. As the acid ‘eats into’ the metal, the areas covered by the rosin are protected. This creates a very even pattern that would be incredibly difficult to replicate by hand. During the printing process, this pattern of corrosion from the acid is where ink settles. If the surface is heavily etched, it holds a lot of ink and makes a very dark (or saturated) area of the print. The opposite is also true, and every degree in between is a different density of ink (think of every shade of grey between black and white).

For these reasons, aquatint printing is often compared to watercolour painting, in that the final image can be very expressive and organic. These qualities make the prints an effective conduit for conveying emotion. When combined with the crisp lines of intaglio and Blackwood’s poetic imagination, you have the perfect medium to tell a deeply moving story that impacts deeply upon one's conscience.

Roughly 28 years after the SS Newfoundland disaster, on November 2, 1942, the British Commonwealth found itself mired in the Second World War. Owing to its ore resources and position along the vital trans-Atlantic convoy routes that brought supplies overseas in support of the war effort, Newfoundland, and in particular Bell Island, found itself a target for German attacks. In fact, Bell Island is one of only a small handful of North American locations that were directly attacked by the Germans during the war.

The first attack occurred on September 4-5. After noticing the frequent traffic of steamers coming in and out of Conception Bay, NL, an attentive German U-boat moved up toward Bell Island undetected. After waiting in the depths of the water overnight, the submarine U-513 rose close enough to the surface to use its periscope and swiftly sank the SS Lord Strathcona and the SS Saganaga. 29 lives were lost in the attack.

The second attack took place on November 2. This time, U-518 had to manoeuvre quickly to avoid the heightened defences that were installed after the first attack. After missing one ship and hitting the dock with another torpedo, the third projectile hit the SS Rose Castle and sent it to the bottom with 28 men. A second ship, P.L.M. 27, was also sunk one minute later, killing 12 men. In 2013, divers from the site Wrecks and Reefs visited the Rose Castle wreckage and documented what remains of the ship. You can view these images here.

In Helloland!, the connection to the Rose Castle is a fantastic Morse Key (also known as a telegraph or wireless key) that was previously installed on the ship. A Morse Key is a specialized piece of equipment that enables trained operators to send messages using Morse code. By pressing the handle down, operators can activate and deactivate a signal. These pulses translate into the ‘dits’ and ‘dahs’ of Morse Code, which is decoded by a receiver elsewhere. This particular key is on loan to us from the collection of the Bell Island Community Museum, where it was donated by Mr. Bob O’Donnell.

Whether it is an original artifact from the source, or a ruminative illustration of history through the eyes of an artist, wireless communications technologies bring these two stories together in Helloland! Art, War and the Wireless Imagination. In one case, the technology is absent, while in the other, it is one of the few elements that remains present. Together, these devices are yet another thread weaving Newfoundland and Labrador into the heart of the global wireless imagination upon which the exhibition is built.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Helloland! Art, War and the Wireless Imagination. Featuring three prints by David Blackwood. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle 1: Robert Palfrey Holloway, SS Newfoundland, 1914, lantern slide. Holloway family fonds, The Rooms [LS 47].

Middle 2: Installation view: David Blackwood, (l) Vision of the Lost Party, 1967, Aquatint etching; (r) Vision of the Lost Party, 1964, etching. Memorial University of Newfoundland Collection, The Rooms.

Bottom: Morse Key from the SS Rose Castle, c. 1942. Wood, steel, brass. Collection of Bell Island Community Museum, Donated by Mr. Bob O’Donnell. Photo by The Rooms.

March 24

Michael Waterman

Non-hierarchical chance operations

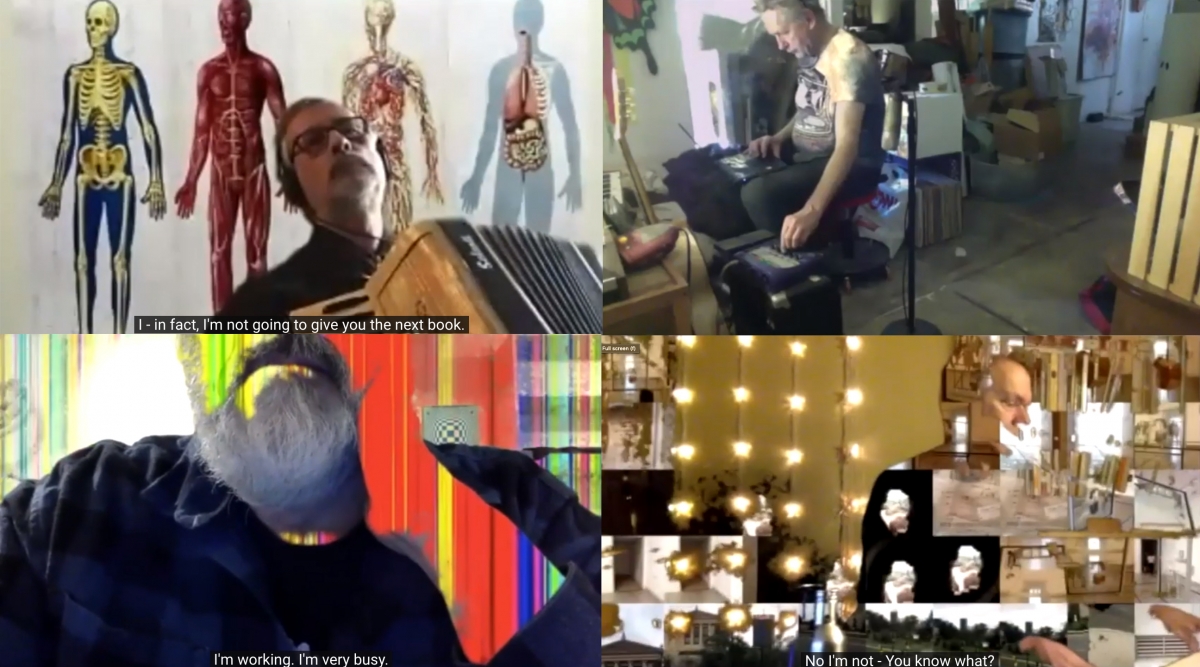

So far in this series, we have been looking at wireless imagination(s) through discrete forms of physical assets or products: radomes, radar sites, shortwave radios, hydrophones, or a high-flying kite with an antenna. These developments have also been socially contextualized. Examples include the impact of radio stations and radar sites on individuals and communities, or environmental impacts requiring remediation and greater global awareness. In Radio Rhizome, the brand-new installation by Michael Waterman, technologies of wireless communication (Zoom meetings and radio broadcast) meet strategies of improvisation to produce spatialized soundscapes within the architecture of the gallery.

Waterman is a visual and sound-based artist whose work focuses on sound installation, improvisational performance and radio art. In 2010, Waterman described his audio art practice:

“[It] has always been concerned with real time, social and visceral experience. It is rooted in my long-running sound art collective, Männlicher Carcano, which has been collaborating continuously for 25 years. In our early years in Winnipeg, our output mostly took the form of Fluxus-style performance art events in which we layered sounds from a number of mechanical, recorded and acoustic instruments, often in a semi-autonomous manner. We presented ourselves as Dada-technicians tending a slightly unwieldy machine (often with costumes and sets), but by the early 1990s, the three founding members had all moved to different cities. This forced us to develop other forms of collaboration. Most enduring has been a weekly multi-city improvised radio show, The Männlicher Carcano Radio Hour, which itself has been running continuously for 15 years and currently involves up to a dozen regular collaborators. Like our early performances, the radio shows usually consist of densely-layered and evolving sound collages.” [1]

For Radio Rhizome, Waterman developed three audio-visual nodes within the gallery. Each node consists of several components. Hanging from the ceiling is a directional speaker with a coloured LED strip and handmade sound baffle. A tablet, mounted on a stand, plays a looped video. The media player driving each node is loaded with an audio track, and each track in the installation is a different length. Together, these components encourage visitors to physically explore the installation to fully experience the artwork. Moving around the space, visitors navigate a complex soundscape as each directional speaker is audible to a different degree depending on where you are in the room. Standing in the very center of the room, you can simultaneously hear a blend of all three audio signals. As the audio coming from each speaker is a different length, the final product is a complex soundscape where no two viewers will ever hear the same thing twice. Even if you visit with a friend and you are in the space together, you will still have a unique impression due to the position of your body in relation to the directional speakers.

Another way to think about Radio Rhizome is from the perspective of Männlicher Carcano. Working together since the 1980s, Männlicher Carcano is a performative audio art collective and polycephalic (an organism with more than one head) host of the weekly Männlicher Carcano Radio Hour. The group consists of three core members that create improvisational performances, recordings and radio art using samples, distortions, loops, vocal utterances and DIY instruments. Their weekly radio show is billed as “the longest running social distancing creative project in the known universe, as well as the highest rated improvisational audio collage radio broadcast originating from St. John’s, Newfoundland!” You can listen to the radio program in St. John’s, NL and online, every Saturday from 4:00-6:00 pm (NST) on CHMR 93.5 FM. Throughout the pandemic, the group has also grown into the visual realm, live broadcasting their improvisational radio program every week on Zoom.

Returning to Radio Rhizome, each of the three pods in the installation can be thought of as one of the core members of Männlicher Carcano. The technological apparati stand-in for the fleshy performers in an unpredictable sonic moment propelled by an anarchistic impulse that underscores much of the group's activities. This impulse extends to their radio program where anybody is welcome to join for one or more performances, and all participants are free to make whatever noise they want. Building on this sense of individual potential, the title is a clear reference to the rhizome theory of French philosophers and psychoanalysts Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. In Radio Rhizome, the rhizomatic soundscape is non-hierarchical and has no beginning, end or middle. It allows for multiple entry and exit points, physically and conceptually.

After all of this talk about signals, nodes and improvisation, Radio Rhizome is really an invitation to play. Ultimately, play is an individually established (or collectively agreed upon) set of behaviours within a strictly defined context. Here, the installation provides the context (three speakers, three videos, one room) and it is up to you to play in the space by moving around and exploring the sound to receive a soundscape that is uniquely your own while also viewing the videos. As the exhibition continues, we are hoping to use one of the tablets to stream the weekly radio improvisations. In this way, visitors would be given the agency to contribute any audio of their own to the performance and radio broadcast by making live sound in the space.

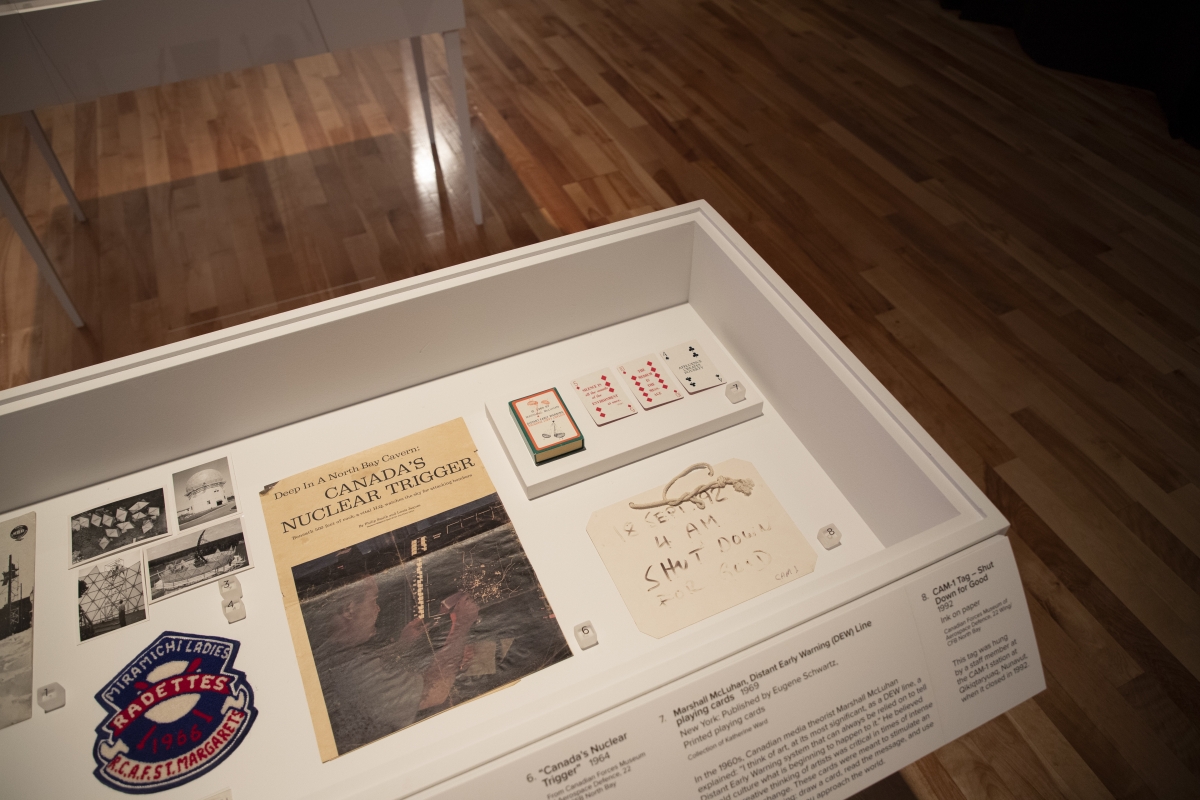

Our historical object of the week also employs a strategy of non-hierarchical chance operation. In the 1960s, Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan said: “I think of art, at its most significant, as a DEW line, a Distant Early Warning system that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it.”[2] He believed that the creative thinking of artists was critical in times of intense technological change. From 1968-1970, McLuhan published The Marshall McLuhan DEW-Line Newsletter with New York publishing entrepreneur Eugene Schwartz. The newsletter was intended to be “an early warning system for the changing age we live in.” Initially, more than 4,000 people subscribed to the newsletter for an annual fee of $50. [3]

As part of the subscription, a deck of playing cards was eventually commissioned. Aimed at decision-makers, influential people, and anybody with a life question, these cards were meant to stimulate lateral thinking. Each card featured well-known quotes by McLuhan and several other influential theorists and artists. Users were intended to think of a personal or business problem, draw a card, read the message, and then apply the quotation to their particular situation. While some quotes could be productive in this way, others seem to be of little use and perhaps allude to McLuhan’s love of jokes and witty one-liners. Some of the messages include:

When all is said and done, more will have been said than done (4 of spades)

“The chicken was the egg’s idea for getting more eggs,” Sam Butler (2 of diamonds)

A man wrapped up in himself makes a small package (8 of hearts)

“Silence is all the sounds of the environment at once,” John Cage (5 of diamonds)

The medium is the message (10 of diamonds)

In the context of Helloland!, McLuhan's divinatory cards uniquely distill the pervasiveness of the wireless imagination as represented by the DEW Line. The deck shows technologies reach into popular culture, and highlights some of the ways that leading figures of the time were thinking about wireless surveillance and prevailing cultural trends. Lastly, the deck embraces indeterminacy and encourages a user to play, just like Radio Rhizome.

Scans of the full deck of cards are available here.

You can order your own deck from Marshall McLuhan’s son here.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view: Michael Waterman, Radio Rhizome, 2020-21, Directional speaker, mixing bowl, felt, tablets, microphone stands, sound, light. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle 1: Michael Waterman, Radio Rhizome (video screenshot), 2020-21, Directional speaker, mixing bowl, felt, tablets, microphone stands, sound, light. Courtesy of the artist.

Middle 2: Collage of The Männlicher Carcano Radio Hour on January 16, 2021. Collage generated by the author. Original video hosted by Doug Harvey.

Middle 3: Installation view featuring Marshall McLuhan, Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line playing cards. Published by Eugene Schwartz, New York, 1969. Collection of Katherine Ward. Photo by The Rooms.

Bottom: Installation view, Marshall McLuhan, Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line playing cards. Published by Eugene Schwartz, New York, 1969. Collection of Katherine Ward. Photo by The Rooms.

Sources:

[1] Michael Waterman, “Robochorus: An Invitation to Play,” Fast Forward Project, Sarnia, ON: Gallery Lambton (now Judith & Norman Alix Art Gallery), c. 2010. Accessed March 17, 2021.

[2] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964.

[3] McLuhan Galaxy, Marshall McLuhan’s DEW-Line Newsletter (1968-70). https://mcluhangalaxy.wordpress.com/2014/05/10/marshall-mcluhans-dew-lin.... Published May 10, 2014. Accessed March 17, 2021.

March 17

Maureen Gruben

Presence

Maureen Gruben was born and raised in Tuktoyaktuk, Inuvialuit Settlement Region, NWT. Tuktoyaktuk was also home to BAR-3, one of the western DEW line radar stations. Her childhood experience sewing with her mother and trapping with her father is evident in the work Survival, which combines sewn sealskin, deer hide, and textiles to create a grid of hybridized military medals.

Subsistence hunting continues to be important for cultural life, food security and understanding ecosystem changes in Inuvialuit. In recent years, Inuit elders and hunters have shared their knowledge about the seal population with the scientific community, in part to understand the effects of contamination on the animal population. Gruben’s minimalist grid is both homage to the hunters and caretakers of the land over millennia, as well as recognition of how the militarization of the North is intertwined with that history.

Gruben’s work harbours a personal activism and leaves space for materials to bring their own significance to bear. Critical links are established that consider life in the Western Arctic alongside broader environmental and cultural questions. These links are often made by combining specific materials (and material histories) in a single work. In this case, materials like sealskin are brought together with colourful swatches of ribbon from military medals. In more ways than one, this is a pivotal work in the exhibition. The complicated modern relationship of Southern interests and Northern needs is, in part, exemplified by the development of the BAR-3 site as a type of wireless imagination. Gruben reflects on that development, and the military presence on her home lands, from the perspective of an individual and family that lived through those changes. While the rest of Canada and the United States was protected by an unseen technology scanning the Arctic skies, the residents of Tuktoyaktuk actually lived with the environmental and infrastructural impacts that came with that perceived safety.

Sometimes, it can be too easy to consider technology or infrastructure exclusively from a technical perspective. It is often much more meaningful to listen to individuals and communities that are directly connected to and impacted by this sort of infrastructural development.

For the archival image of the week, we have a reproduction of a Plan Position Indicator (PPI). This particular image of a PPI is from the National Research Council of Canada Archives. Essentially, a PPI is the most common type of radar display. In this type of display, the radar antenna is ‘located’ in the middle of the screen. The direction of the radar is represented by a thin line that rotates around the screen as the antenna physically rotates in its radome outside. The concentric rings represent distance from, and height above, the antenna.

As the radar antenna ‘sweeps’ the skies, it sends out signals that reflect back to the antenna when they encounter different materials. These return echoes are mapped on the PPI for a technician to interpret. While the first PPI was used prior to the start of the Second World War, the technology has many uses today, including meteorology, air traffic control, and on various vessels like aircraft, ships and submarines. On the DEW Line, these screens were like portals into the future or into the distance, letting technicians know what was in the air, where it was in the sky, what direction it was coming from or moving towards, and at what velocity. Quite a task for a relatively rudimentary looking display!

Lastly, throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, Canada’s North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) converted a number of the original DEW Line sites to a more modern North Warning System (NWS). BAR-3 in particular was converted in September 1990. The NWS officially went online on July 15, 1993. Environmental remediation work on the BAR-3 radar site was completed in 2005. After remediation, the site now consists of a radar tower for the NWS, a communications facility, a smaller storage location and the gravel remains of previous roads and foundations. It continues to operate as an unmanned NWS site. You can see an image from Google Maps of the overall location below, or visit this website for photographs from the ground.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Maureen Gruben, Survival, 2018, sealskin, beads, deer hide, ribbon and metal clasps on canvas. Private Collection. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle 1: Maureen Gruben, Survival (detail), 2018, sealskin, beads, deer hide, ribbon and metal clasps on canvas. Private Collection. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle 2: Installation view, Plan Position Indicator (PPI) Radar Display, 1965-70, digital reproduction. Collection of the National Research Council of Canada Archives.

Bottom: Google Maps screenshot of the BAR-3 site in Tuktoyaktuk, Inuvialuit Settlement Region, NWT. Screenshot by author, 10 March 2021.

March 10

Margo Pfeiff

Construction, Deconstruction

The construction of the DEW Line was an incredible feat of engineering and logistics. Some 25,000 individuals were employed in the construction of the network. They built facilities, roads, antennas, airfields, and storage hangers, fed the crews, managed inventory and accomplished all of this in extreme environmental conditions. With Cold War tensions rising, the primary focus was on getting the network operational as quickly as possible. Security interests took precedence over concerns about the environment and life in Northern communities. With all of its many successes, the DEW Line also became an environmental disaster.

Construction and operation of DEW radar stations involved industrial materials that eventually contaminated the land, leaching into the permafrost and the Arctic food chain. PCBs, hydrocarbons, lead, mercury, asbestos and antifreeze were some of the products and by-products that were not properly disposed of. As the first stations were decommissioned in the early 1960s, rusting hulks of equipment were left abandoned, and sometimes pushed into the ocean. For years, Inuit brought home tools, furniture and other materials from the sites without knowing they were contaminated.

There was not the same attention to and awareness of environmental health as there is today. The mission at the sites was clear - to watch the radar for any incoming airborne threats. Keeping the Arctic clean was not a priority. In Fixing the Mess, Margo Pfeiff shares a story from Martin Allinson, a young electrical engineer who worked as a radar and radio technician on the DEW Line in 1959. Allinson remembers the “bored military boys’ 45 gallon drum rolling competitions on a wide slope beside Cape Dyer’s radar dome. Since the heaviest ones rolled farthest, full barrels of gasoline and lubricating oil were pitched down the hill with particular enthusiasm.”[1]

In 1989, environmental remediation of the sites began. This work was primarily completed by Inuit-led companies, commissioned by the Department of National Defence. Each site was found to have a pollution ‘halo’ of approximately 20 kilometers. “With the DEW Line sites 80 kilometers apart, many with Inuit settlements alongside, there was a continuous corridor of pollutants right across the Arctic and potentially in the food chain.”[2] The clean-up ultimately took 17 years and cost $575 million, making it one of North America’s largest environmental remediation projects ever.

Margo Pfeiff’s photographs document the clean-up of one of the largest Canadian DEW line sites, the 28,000-acre Cape Dyer site on Qikiqtalluk, Nunavut. The images capture so-called “Goody bags” full of PCB-contaminated soil that was removed from the sites and shipped south for incineration. They show rusting metal components from abandoned infrastructure and the huge mechanical and human resources required to complete a project at this scale. But they also capture something else: the unfathomable scale and presence of the land. The series oscillates between factual index and abstract beauty; of gritty minutiae and ethereal vistas. It reminds us that these wireless technologies and hidden infrastructures all exact a toll upon the lands in which they are positioned.

For more, please read Pfeiff’s short article Everyone Just Left from the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA).

For the archival part of this week's post, we go back in time. After all, you have to build the thing before you can take it down and clean it up! These four photographs (below) are part of a larger collection from the Secrets of Radar Museum in London, ON. They show aspects of the process of constructing a radome. Each spherical structure is composed of many individual triangular units. The modular system not only made construction very efficient, but also provided an architecture that distributes tension and compression through the latticed network of structural supports. This makes the final form extremely resilient and, in this case, able to resist the environmental conditions of the Arctic.

These particular photographs were taken by Charles Young. In the late 1940s, Young worked for Marconi Canada and then Northern Telecom (later NorTel). He became a civilian contractor involved in the construction of the Pinetree Line radar stations throughout Eastern Canada, where he captured the images in this exhibition.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Margo Pfeiff, Environmental Ruin, 2020, inkjet photographic prints, Collection of the artist. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle: Margo Pfeiff, Environmental Ruin: Upper Base, Cape Dyer, 2020, inkjet photographic prints. Courtesy of the artist.

Bottom: Installation views, How to Build a Radome, c. 1955, Gelatin silver photographs, Collection of the Secrets of Radar Museum, London, ON: From the Charles Young Collection. Photo by The Rooms.

Sources:

1. Margo Pfeiff, “Fixing the Mess,” Up Here, October-November 2012 (Yellowknife, NT: Up Here Publishing) 55. Accessed digitally 2 March 2021. https://margopfeiff.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/dew-line-clean-up-uh.pdf

2. Ibid., 59.

March 3

Qavavau Manumie

Grounded Signals: Wireless Infrastructure on the Land

A wireless imagination contains a certain utopian promise. It promises to get rid of the cables strung along our streets, wrapping around our homes and tethering every device. Life is supposedly cleaner, faster and more efficient. Increasingly, our cell phones relay staggering amounts of data for voice calls, internet searches, GPS directions, near-field communication transfers, and so much more. With all of this supposed convenience, it is easy to stay blind to the physical infrastructure (like data storage farms) required to make this imagination a reality. A wireless system is never without wires - they are just kept out of sight.

For all of its benefits, the infrastructure that facilitates wireless transmission brings a number of drawbacks. Most notably, they alter the environment in two direct ways. They impact the lands upon which the infrastructure is built and maintained, and they increase global carbon emissions from the production of materials and the ongoing operation of required technologies. As these networks become more widespread and accessible than ever before, it is important to think about the sustainability of future development and the consequences of modern convenience.

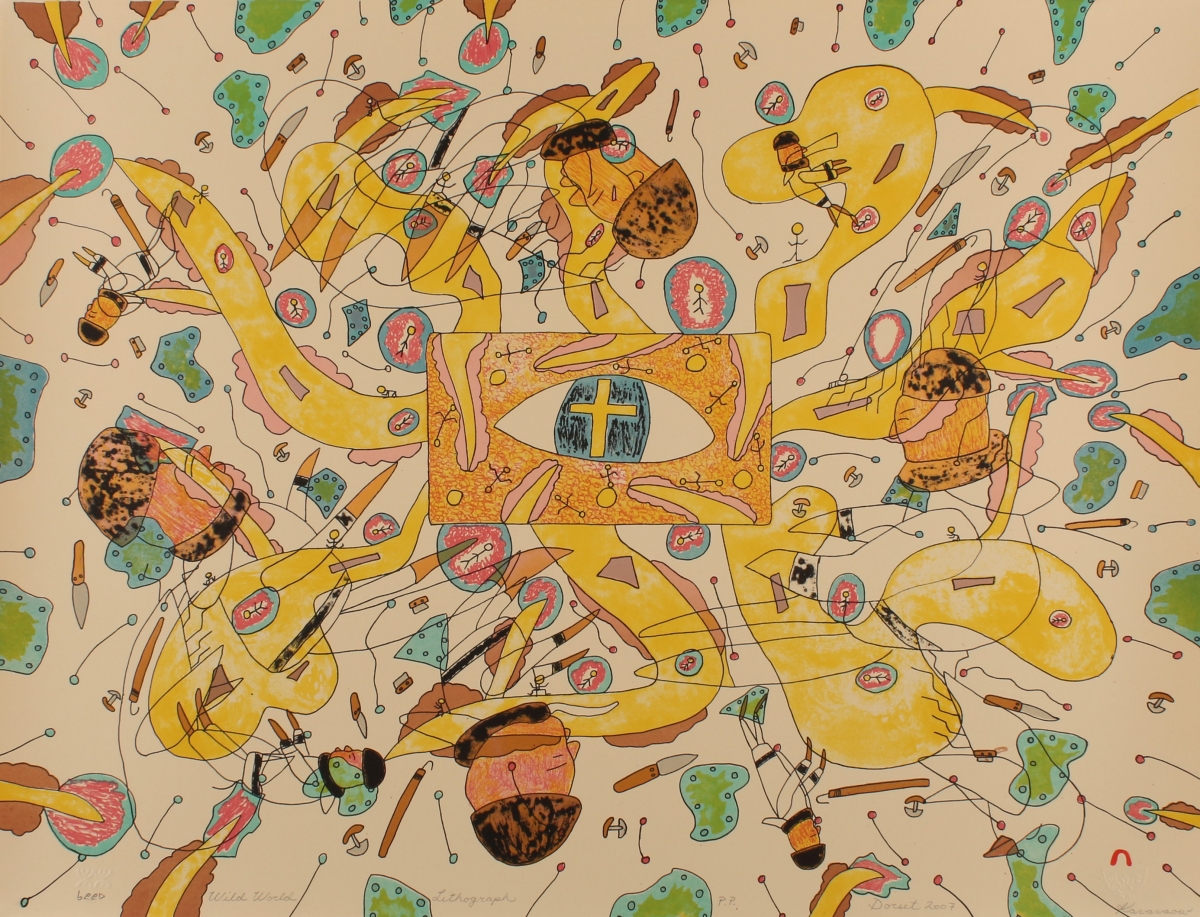

Qavavau Manumie is a Kinngait, NU, based artist who is best known for his drawing and printmaking. He began drawing in his late teens and is part of a generation of artists that are expanding the subject and form of contemporary Inuit art. Common subjects in his work include the natural environment, familiar objects and activities from daily life. These are often imbued with humour and an original creativity.

As noted on the Inuit Art Foundation website: “His landscapes are also politicized… The warming environment is emphasized. Manumie’s work combines both gritty scenes of reality and fantastical scenes taken from the artist’s imagination.” These characteristics are both readily apparent in Wild World (above) and Composition (Melting Arctic) (below). Manumie represents the melting Arctic as a product of unfettered industrial development. Human and animal forms find themselves disconnected from each other and from the rest of the land. As the ice fragments and falls apart, the only thing holding it together is individual will. It seems that traditional tools and practices must be mended, remembered and strengthened in order to survive.

In thinking about wireless infrastructure and the impact on the land, we turn to the publication DEWLINE POLAR ECHOES. It was published by the Federal Electric Corporation which received a contract from the United States Air Force in 1957 to operate and maintain the Distant Early Warning Line radar stations. This publication was for their employees. A January 1959 issue of Polar Echoes states their mission: “To operate and maintain the land-based segment of the DEW Line at maximum efficiency, on an austerity basis, in order to detect, evaluate and report to the Air Defense Commanders all airborne objects entering or operating within the DEW Line Identification Zone.”

The publication captured ongoing business operations and the life of the staff. Segments included News from the Line, Safety Tips, updates on corporate initiatives (such as providing materials to Amateur Radio Operators on staff) and personnel stories like My First Trip to the DEW Line and At the Foot of the Mountain. The publication also featured photography from radar sites and occasionally included Inuit from the regions. These inclusions, however, often establish a tenuously colonial relationship. For example, the January 1959 cover juxtaposes an airplane landing (or taking off) over an Inuit dog sled team.

DEWLINE POLAR ECHOES was ostensibly a corporate communications tool (slogans included “Make Haste Slowly” and “Safe Construction Prevents Costly Destruction”). Looking back with a critical historical eye, the publication can be a useful primary source in understanding day-to-day life of DEW employees.

For a look inside one of these radar sites, check out the 1953 short film Radar Station from the National Film Board.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Helloland! Art, War and the Wireless Imagination. Featuring work by Qavavau Manumie. Photo by The Rooms.

Upper Middle: Qavavau Manumie, Wild World, 2007, lithography, William B. Ritchie Collection, The Rooms. Photo by The Rooms.

Lower Middle: Qavavau Manumie, Composition (Melting Arctic), 2019, coloured pencil and ink on paper, Royal Bank of Canada Collection. Photo by The Rooms.

Bottom: Installation view, DEWLINE POLAR ECHOES, published by Federal Electric Corporation, Paramus, New Jersey, April 1957. Collection of Melony Ward. Photo by The Rooms.

February 24

Charles Stankievech

Distant Early Warnings: Wartime Origins and Utopian Dreams

“A border is not a connection but an interval of resonance, and such gaps abound in the land of the DEW Line. The DEW Line itself… points up a major Canadian role in the twentieth century, the role of hidden ground for big powers. Since the United States has become a world environment, Canada has become the anti-environment that renders the United States more acceptable and intelligible to many small countries of the world; anti-environments are indispensable for making an environment understandable.”

Marshall McLuhan

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line was part of a continental radar defence system built during the Cold War. It was a joint US/Canada operation, designed to detect incoming Soviet nuclear missiles and to communicate information to NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense) command in the south. The DEW stations became operational throughout 1956 and 1957 and eventually formed a northern border comprising 63 sites along the 69th parallel, stretching from Alaska, across Canada and into Iceland.

The first geodesic dome was originally constructed in the 1920s in Jena, Germany, to be used as a planetarium; the term ‘geodesic’ wasn’t coined until the late 1940s by Buckminster Fuller at the experimental Black Mountain College. Fuller is credited with the popularization of the geodesic dome in North America and his original designs have become icons of modern utopian architecture. For the DEW Line, Lincoln Labs collaborated with Fuller to design a rigid geodesic radome that would be electromagnetically invisible to the antennas inside. The dome kept the sensitive instruments protected from the harsh Arctic environment while remaining invisible to their signals.

Fuller is often associated with utopian thinking. He developed frameworks for using the world's resources in an efficient and egalitarian way in order for humanity to survive: the world only works if the world is doing well. In the context of the DEW Line, Fuller’s radomes played some part in avoiding the Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) of that very world.

A single spherical dome articulates an infinite boundary between inside and outside. Inside, there is safety and protection from the elements and when sheltered within, the impressive architecture can metaphorically expand to become a whole world. It becomes a planetary and cosmic volume. Similarly, a network of radomes draw a border of inside and outside. This border, however, is enforced by political interest, military might, and social need, and was made visible through dichotomies of us and them, good and evil, survival and collapse.

As Charles Stankievech notes, “The geodesic radome is the ultimate metaphor symbolizing the shift in modern warfare in the second half of the 20th century: an architecture that distributes its structural tension and compression through a network similar to the communication network it shelters.”(1) In his artwork, The DEW Project, Stankievech revisits the issue of boundaries – both in regards to the environment and sovereignty – while observing how communication technology plays a pivotal role in defining and delivering such ideologies. Here, the geodesic dome remains a symbol of invisible military communications, counter-cultural utopias and recalls another efficient type of polar structure: the igloo.

The artwork includes four main components. The first consists of a large glowing dome, an antenna, three solar panels and some wires. These were used in the initial field installation of this project in the Yukon. A field installation is defined as:

“A work of art that takes into account the geographical site comparable to a strange attractor that warps one’s perception of the space. Sharing the history of “art installation” which takes into account the architecture of the site and the viewer’s phenomenological position, a field installation creates its own temporary architecture within a space or in a landscape. Such architecture, however, might not always be a traditional shelter, but can include sonic material, electromagnetic fields, light projection, or relationships.”(2)

Resting on the frozen confluence of the Yukon and Klondike Rivers, these objects originally formed a listening station and recorded underwater sounds with hydrophones. These sounds were broadcast on a Dawson City radio station and over the internet. Today, excerpts of the audio are the second component of the installation. This soundtrack was also released as a composition by Musicworks (Issue 106) and accompanies the third component of the artwork: the video. The video documents aspects of the artists’ fieldwork, including: a windy Arctic expanse illuminated by the setting sun; ice pans flowing down a river; various antennae and associated infrastructure; the artist recording audio, visiting sites; and the pulsing light of the glowing dome.

The fourth component of The DEW Project is a comprehensive online archive. Stankievech collaborated with David Neufield, Yukon and Western Arctic Historian for Parks Canada, to develop the The BAR-1 DEW Line Archive. This rich resource brings together Neufeld’s 20 years of research on the BAR-1 station. Here you can browse over 200 images, 300 blueprints and a collection of critical essays exploring site construction, modes of life and operation of the site.

Artworks like The DEW Project offer many points of entry. One is retrospective and considers the past through archival research, experiential depth and critical reflection. Another is situated in the present as a constellation of objects, images and sounds in the gallery, and in relation to current global issues. Yet another looks out toward the future. Here, we can ruminate on a number of subjects: how will the so-called Warm War (over natural resources in the North and sovereignty in a rapidly melting world) end, or has it even begun; what are the legacies of our contemporary architecture; where will the lines and networks of surveillance and wireless communication be inscribed next, and what will their effect(s) be?

Lastly, the archival object for this week is from Athens, Greece, c. 1960. The card features an illustration by Ioanna Athanasopoulou of a Canadian DEW line site. The futuristic imagination of a distant, unfamiliar land includes penguins roaming the Arctic ice. Of course, penguins do not live in the Arctic! Nonetheless, the image distills a certain utopian promise of military technological development and architectural evolution: a future where a population can feel protected by unseen technology in the North.

For more about the DEW Line, listen to the January 2021 podcast from Canada’s History, Cold War Tech and Its Discontents, produced by Melony Ward with assistance from Sarah Martin.

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Charles Stankievech, The DEW Project, 2009, geodesic dome, 3 solar panels, antenna, HD video and sound, 13:46 minutes. Collection of the artist. Photo by The Rooms.

Upper Middle: Charles Stankievech, The DEW Project (installation view), Confluence of Klondike + Yukon Rivers, Yukon Territory, Canada. 64o03’ N, 139o27’ W. Courtesy of the artist.

Lower Middle: Charles Stankievech, Field Recording on the Beaufort Sea, near Tuktoyuktuk, Northwest Territories. 69o26’ N, 133o00’ W. Courtesy of the artist and F. Jamison.

Bottom: Installation view, Trading Card with Artist’s Impression of Northern DEW Line Installation, c. 1960, printed card from Athens, Greece. Collection of Melony Ward. Photo by The Rooms.

Sources:

1. Charles Stankivech, “Cinema, Gramophone, Radio: A Quiet History” in Canadian Electroacoustic Community, eContact!, 11.2 (Concordia University online, July 2009) Accessed February 8, 2021.

2. Ibid.

February 17

Brian Groombridge

The Power of Form, a Form of Power

If I ask you to “think of the radio,” what comes to mind? Do you remember listening to a favourite program on the radio, discovering a new band, or following a significant world event in real-time? Do you picture a radio that you had growing up, or one that you still listen to at home? Or do you first lean toward a more abstract concept of what radio is? Radio can be a tangible object, a familiar memory and an iconic symbol of communications and information exchange. It is both form and function, transitory and provisional.

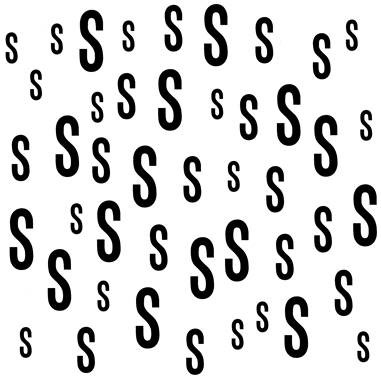

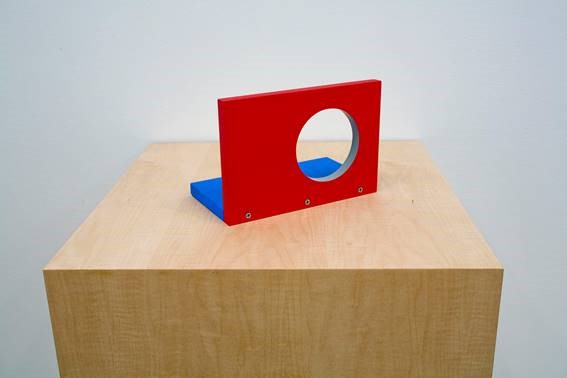

In these works, Brian Groombridge explores the history and form of radio. Marconi Whisper (above) brings us back to the first wireless trans-atlantic signal that Marconi received on Signal Hill in December 1901. Marconi’s team raised an antenna more than 500 feet into the air by a kite. After several attempts, Marconi picked up the receiver and heard three quiet pulses: Dit-dit-dit. It was Morse code for the letter S. In Groombridge’s print, the bold, condensed, sans serif font (wherein all parts of the stroke are an optically uniform thickness) mimics the consistency of the Morse code pattern. The print is hung higher up on the wall, aerially tethered to the exhibition like the receiver of Marconi’s S’s.

Untitled (below) is a small, sculptural construction detailed in a red, blue and yellow colour palette of the Dutch movement, De Stijl (1917-1931). The movement advocated for universality by reducing form and adornment to the essentials. This work alludes to the form of a radio, a site of transmission, with the fullness of a sign, but no signal. It is a classic case of Groombridge’s reductionism as we work to decipher the visual codes embedded within. As Charles Reeve noted: “All art speaks in code. Obscurity and clarity are functions of knowing or not knowing a particular code, not of whether a given work is coded. Beyond that, what seems obscure in Groombridge’s work actually is the metaphorical point: a message that, drained of purpose, goes nowhere.”

Not far from Groombridge’s work is a shortwave radio from the 1930s. As an object, it’s incredibly warm and inviting. Its warmth stems from the well-worn wood, the soft brown fabric on the speaker grill and the tiny ship illustrated in the middle of the dial. The object wonderfully contains its material history - one can only imagine how many broadcasts it received over the years. Its basic form also appears as a loose template for Groombridge’s sculpture: both objects have one circular portal in roughly the same spot.

Shortwave radio is different from the AM or FM broadcasts that we most often hear today. It is a specific type of radio transmission using wave frequencies that can be reflected off of a layer in the atmosphere. This means that shortwave radio broadcasts can travel far beyond the horizon; they overcome geographical and political boundaries.

Since transmissions can be received thousands of kilometers away from the transmitter, the technology is often used to distribute information within geographically isolated or politically censored communities where information may not otherwise be widely accessible. These characteristics of shortwave radio imbue it with a certain democratic promise and potential, to freely distribute information and communicate with others around the world.

Where Groombridge revels in the power of form, the shortwave radio is a form of power.

Image credits:

Top: Brian Groombridge, Marconi Whisper, 1993, silkscreen on paper, 63.5 x 63.5 cm. Courtesy of Susan Hobbs Gallery.

Middle: Brian Groombridge, Untitled, 2008, painted aluminum and wood, 110 x 40 x 40 cm. Courtesy of Susan Hobbs Gallery.

Bottom: Installation view, Knight A9871 7-tube Shortwave Radio, c. 1937, wood, assorted electronics and mixed media, The Rooms. Photo by The Rooms.

February 10

Jackson 2bears + Janet Rogers

The Political Economy of Sound

“When lawyer Peter Grant asked Chief Mary Johnson to sing a Gitksan song as an essential part of her evidence on the “Ayook,” the ancient but still effective Gitksan law, Judge McEachern objected. He said he did not want any “performance” in his court of law. “I can’t hear your Indian song, Mrs. Johnson, I’ve got a tin ear.”

Most of us non-Aboriginal Canadians also wear a tin ear. It seems natural because we have worn it all our lives. We are not even aware of the significant sound we cannot hear.”

Walt Taylor

The Three Rivers Report, July 15, 1987

Quoted in Dylan Robinson’s Hungry Listening [1]

From the beginning, much of the development of early radio infrastructure across Canada was connected to industry, resource extraction and colonization.

The first large-scale investment in radio infrastructure was by the Canadian National Railways (CNR) Radio Department. CNR Radio began broadcasting in 1923 and continued until it was nationalized, becoming an early version of the CBC in 1932. Generally, the only voices available on the airwaves were colonial dialects of the English and French. The rail lines brought settlers in, carried resources out, and broadcast audio along the way. Occasionally, CNR Radio included content for Indigenous communities that the trains were passing through.[2]

Quite simply, there was not very much programming available for Indigenous communities prior to the 1970s. This specific relationship of broadcast source and intended receiver seems to somewhat relate to the “listening through whiteness” that current Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Arts, Dylan Robinson, writes about in Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies.[3] One company essentially maintained a monopoly on the radio spectrum - if you wanted to be heard, it had to go through them and serve their interests.

This gradually changed over the course of the 20th century as radio licenses became more widely available and nationalist monopolies wore away. The 1970s and 80s, in particular, saw the formation of many Indigenous-led communications organizations and the development of radio programming designed for, and by, their communities. This movement highlighted the importance of Indigenous voices holding space on the spectrum and increasing the audibility of language. Within the province, one example can be seen in OKâlaKatiget Society, a radio station based in Nain, Labrador and incorporated in 1982. In English, OKâlaKatiget translates to “People who talk or communicate with each other.” A primary aspect of their mandate is to preserve and promote the language and culture of Inuit in the region.

NDNs on the Airwaves is a short documentary set in Ohsweken, Ontario. It tells a story about poet and radio host Janet Rogers re-connecting with ‘place’ by finding her voice on the airwaves. It also reveals what community-driven radio represents to the community in that region. The station, CKRZ-FM - The Voice of the Grand - was founded in 1987 and received its broadcast license in December 1991. The documentary positions CKRZ-FM in relation to the mainstream, and asks how the community can Indigenize the medium. They want the airwaves to be a signal that carries people back home and to have a place for their voices to be heard. It is a place for the community to tell their own story, instead of having it (mis)represented by external media platforms.

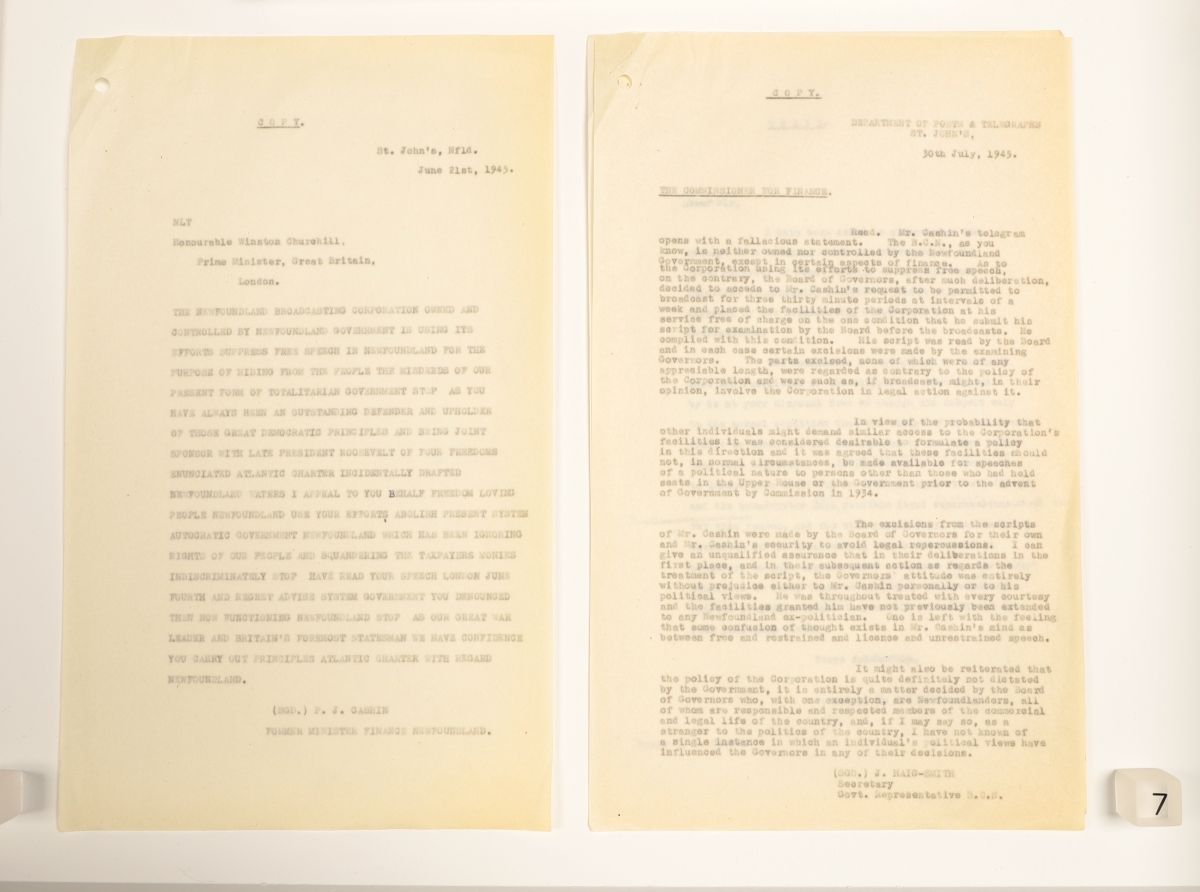

The archival documents for this week demonstrate a different sort of concern for the airwaves. In 1945, Newfoundland was under the control of the British Commission of Government. Coming out of the Second World War and working to reform the economy and population of Newfoundland, the Commission was sensitive to the content of local radio broadcasts. By overseeing the Broadcasting Corporation of Newfoundland (BCN), they directly shaped some of the most popular and widely available programs on the island.

The first letter was written by the former Minister of Finance, Major Peter John Cashin, to British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill. Cashin suggested the BCN was being used to suppress free speech in Newfoundland for the purpose of “hiding from the people the misdeeds of our present form of totalitarian government.” Certainly, Cashin was not only interested in radio - he was adamantly against the Commission overall. Even so, his letter shows an understanding of the power of this form of mass media, and a deep sense of how the technology should serve the receiver and not just the broadcaster.

In a summary response for Prime Minister Churchill, secretary J. Haig-Smith contends that they have done no wrong. He explains that they allowed Cashin to speak at the BCN for three, 30-minute periods, free of charge - though he was required to submit his script for review first. He also confirms that in every case, censures were made. A policy was subsequently developed that prohibited speeches of a political nature on the radio unless it was by an existing high-ranking politician. The letter concludes that the BCN was directly led by the Board of Governors who were, with one exception, all Newfoundlanders, dismissing any suggestion that Cashin should be upset with the Commission in this regard.

Sound is a political tool. Listening, audibility and intention are intersectional processes that weigh upon the original sounding body and the receiving one. It is a process that involves bias, habit, lived experience and veritable truth. But it isn’t just a technical process; it is one that can also touch the feelings of the listener and move them.

View the short documentary by Jackson 2bears and Janet Rogers here:

NDNs on the Airwaves

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Jackson 2bears and Janet Rogers, NDNs on the Airwaves, 2015, HD video and sound, 11:59 minutes. Produced by Janet Rogers and directed by Jackson 2bears. In partnership with the National Screen Institute, National Film Board of Canada and the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle: Jackson 2bears and Janet Rogers, NDNs on the Airwaves (still image from documentary), 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Bottom: Installation view, Letter from Mr. Cashin to Sir Winston Churchill, June 21, 1945, ink on paper, The Rooms; Letter from Representative to Sir Winston Churchill, regarding Cashin Letter, July 30, 1945, ink on paper, The Rooms.

February 3

Marc Losier

From the Depths of the Ocean

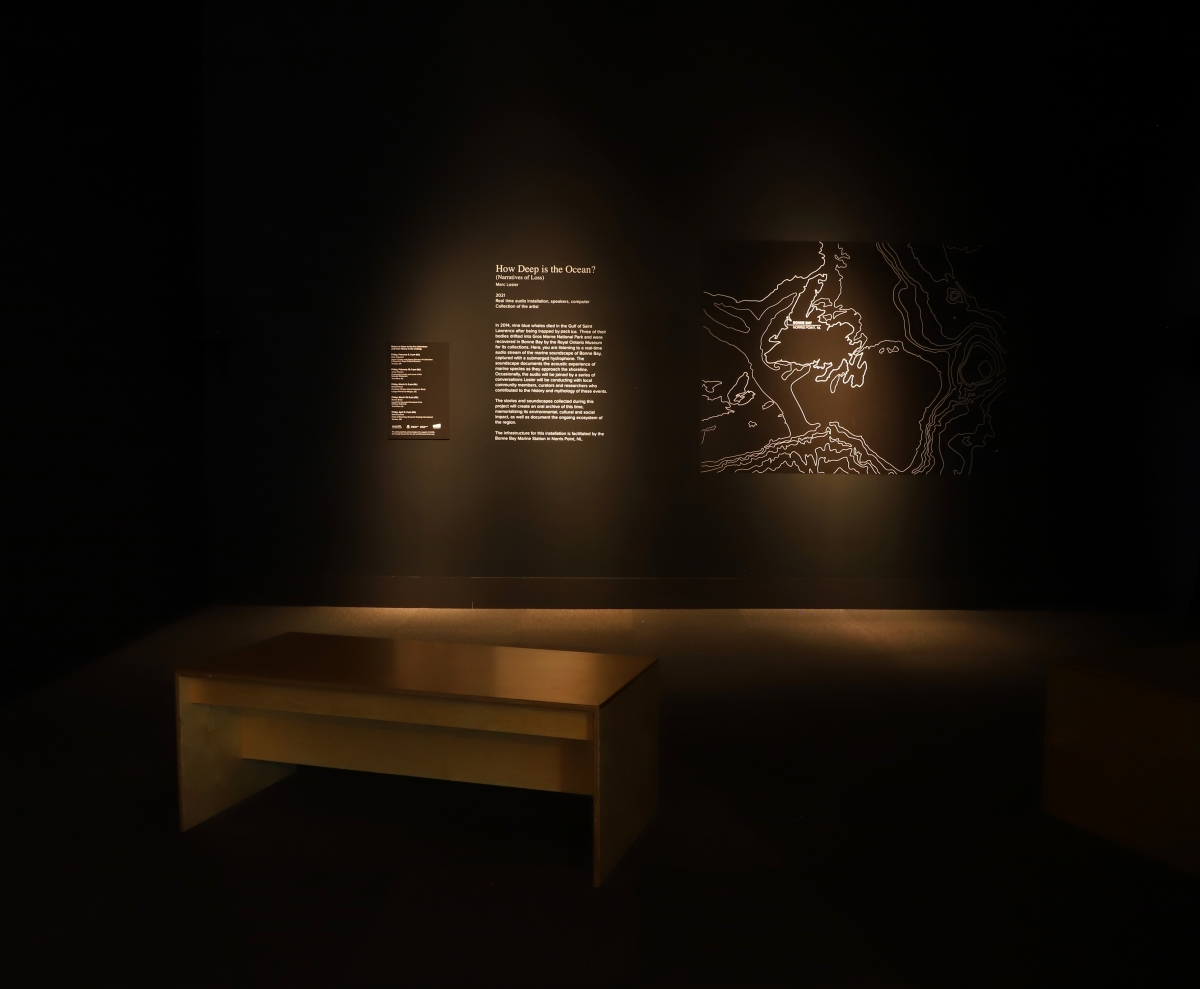

In 2014, nine blue whales died in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence after being trapped by sea ice. Three of these bodies drifted into Gros Morne National Park and were recovered in Bonne Bay by the Royal Ontario Museum for its collections.

You may remember reading about the event in stories like these:

Blue whale heart from Newfoundland installed at Royal Ontario Museum

Or perhaps you saw the results in this exhibition:

Out of the Depths: The Blue Whale Story

In How Deep is the Ocean? (Narratives of Loss), Losier broadcasts a real-time audio signal of the marine soundscape of Bonne Bay from a hydrophone installed at a depth of 20m. The soundscape documents the acoustic experience of marine species as they approach the shoreline. Once every two weeks, this audio stream will be joined by live interviews with community members, curators and researchers who contributed to the history and mythology of these events.

The first conversation takes place on Friday, 5 February @ 6 pm with Mark Engstrom, Senior Curator and Deputy Director of Collections & Research at the ROM. Listen to the conversation live in the exhibition at The Rooms, or stay-tuned for a digital upload in the future if you aren’t in St. John’s. The full interview schedule can be found at the bottom of this post.

In some ways, Losier’s project can be seen in the context of oceanic communication; we are listening to the ocean in real-time, hearing indications of industry and the presence of sealife. There is a different sort of link to oceanic communication in the beginning of the exhibition. Here, we present a section of trans-oceanic submarine telegraph cable from Heart’s Content, NL. The other end of this cable was tethered to Valentia Island, Ireland. It became the first lasting link connecting Europe and North America when, after several failed attempts, the original cable was finally brought ashore on July 27, 1866.

Ultimately, the wireless imagination that supplanted the utility of the telegraph cable is the means of transmission for Marc’s project today.

For more about Marc’s project, you can read this interview with the artist:

Listening to the Ocean

Full schedule of Marc Losier’s interviews:

Friday February 5th, 6pm (NST)

Mark Engstrom

Senior Curator and Deputy Director of Collections & Research

Royal Ontario Museum

Toronto, ON

Friday February 19th, 6pm (NST)

Jenny Parsons

Community Leader and owner of the Seaside Restaurant

Trout River, NL

Friday March 5th, 6pm (NST)

Richard Sears

President, Mingan Island Cetacean Study

Longue-Pointe-de-Mingan, QC

Friday March 19th, 6pm (NST)

Bonnie Brake

Local Fish Harvester/President of the Harbour Authority

Trout River, NL

Friday April 9th, 6pm (NST)

Brett Crawford

Head of Mounting, Research Casting International

Trenton, ON

Image credits:

Top: Installation view, Marc Losier, How Deep is the Ocean? (Narratives of Loss), (2020-21) Map, text, sound, interviews. Photo by The Rooms.

Middle: Installation detail, Marc Losier, How Deep is the Ocean? (Narratives of Loss), (2020-21) Map, text, sound, interviews. Courtesy of the artist.

Bottom: Trans-oceanic submarine telegraph cable, Heart’s Content, 1860s, Telegraph cable, The Rooms Museum [974.50.1].

January 28

Reginald Shepherd

GUGLIELMO MARCONI: 20TH CENTURY TECH GIANT

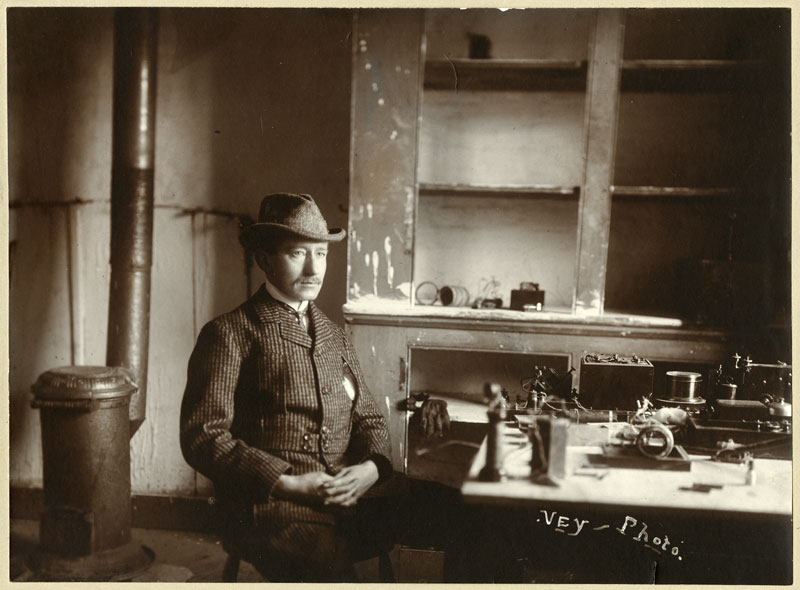

Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937) set out to prove that wireless radio could reach across the Atlantic Ocean. In December 1901, he arrived in St. John’s, NL. His group used a kite to lift a wireless aerial more than 500 feet in the air. In England, Marconi’s team tapped out three dots of Morse Code for the letter “S.” After several failed attempts, Marconi picked up a receiver, heard the three dots, and made history.