A Century of Armed Conflict in Newfoundland

A Century of Armed Conflict in Newfoundland

By Bernard Ransom

Winter 1982

Reprinted Fall 1991

[Originally published in printed form]

From the early 16th century, the proximity of the island of Newfoundland to the phenomenally rich fishing grounds of the Grand Banks resulted in fierce competition for its harbours and anchorages between English migratory fishermen and their European competitors. The profits of the fishery, together with Newfoundland's strategic location astride the navigation route between Europe and the New World, inevitably drew the expansionary powers of Europe into a struggle for its possession.

In the century which followed Sir Humphrey Gilbert's annexation of Newfoundland in 1583, the English fishing merchants and their crews who used the island's coves and harbours had to rely upon their own efforts for defence against armed attack. Such attacks on the migratory fishing fleet were made regularly by foreign and domestic enemies, unscrupulous competitors and international pirates. Armed attack by pirates - especially Turkish marauders - regularly disrupted the fishing season, despite the best efforts of the small English navy of the period. During the English Civil War (1640-49), some sea fighting developed between Newfoundland vessels owned by Royalist fish merchants and ships sent to harass the Newfoundland fishing fleet by Parliamentarian sympathizers in New England. It was only with the establishment of a strong navy under Cromwell's Commonwealth (1649-60) that peaceful conditions prevailed in the Newfoundland trade.

With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the British government continued Cromwell's conflict with Holland for supremacy in ocean-going commerce and, additionally, concluded a secret diplomatic understanding with France. In Newfoundland, this policy permitted the establishment of the first permanent garrison of regular troops in the island: the French garrison at Placentia in 1662. Meanwhile, continued Anglo-Dutch maritime rivalry brought about a renewal of naval warfare with Holland and Newfoundland suffered some of the consequences. Meeting little opposition, a Dutch fleet captured St. John's in 1665, burning shipping and property on shore. Still without naval or military defences, the English merchants of St. John's did what they could for their own defence. After the Dutch attack Christopher Martin, a Devon merchant captain, built and maintained defensive batteries at the entrance to the harbour at his own expense. In 1673 Martin, with fewer than thirty men, successfully defended the harbour from a second Dutch attack and a separate raid by four pirate vessels.

The accession of William and Mary in 1688 brought about a reversal of British foreign policy, but although war was formally declared with France in 1689, little was achieved to give the English in Newfoundland better security from attack. From the Placentia base, the French made successful yearly assaults on the English settlements and fishing stations. An early attempt in 1692 by a powerful fleet of the Royal Navy to destroy the Placentia forts was given up as an impossible task. Two years later, the merchant captain William Holman successfully defended Ferryland harbour from French attack but, the following year, 1695, the French surprised several ships of the English fishing fleet as they gathered for the return voyage: during the resulting engagement, the fleet convoy, HMS Sapphire, was sunk in Bay Bulls harbour.¹

The winter of 1696-7 brought the most ambitious attempt to date by the French on the English settlements in Newfoundland. In the fall of 1696, an expeditionary force of over 400 French regulars, with Indian and French Canadian auxiliaries, was dispatched to Placentia by the governor of New France. This force, under the command of Le Moyne d'Iberville, joined with the Placentia garrison and the crews of a dozen St. Malo privateers then in harbour for a winter assault on the English settlements on the Avalon. This formidable force destroyed all of the English communities on the Southern Shore without serious opposition, but, marching on St. John's, it was engaged on the Southside Hills by a group of 84 local men lying in ambush. For over half an hour this small body of local residents, outnumbered 5 to 1, fought the French and Indians until half of them had been killed or disabled. They then withdrew to a small fortification which had been prepared in the city, where they held out for a further 48 hours. With supplies running short and intimidated by threats of Indian torture, the surviving English surrendered and were shipped home by the French command. The French moved on and, by February 1697, had returned to Placentia, having destroyed every settlement on the Avalon Peninsula except Carbonear.

This signal disaster, and especially the consternation it caused in New England, at last stimulated the British government to provide a permanent defence force for the island. A strong British relief force of 1500 troops reoccupied St. John's in the summer of 1697: they found the town abandoned, pillaged and every building destroyed. The following year construction was begun on a well-engineered fortification - Fort William - which, when completed in 1700, had brick-faced ramparts, bomb-proof parapets, powder magazines and proper barracks.

Peace had been established in 1697, but at the time of the accession of Queen Anne in 1702, war with France was renewed. Thereafter, annual raids were carried out by both the French and English on the other's settlements and fishing stations. It was during one of these raids, made by 150 French and Indians on Bonavista Harbour in 1704, that the New England skipper Michael Gill distinguished himself. With his 24-man crew and 14-gun vessel, Gill successfully fought off the French attackers who used two larger armed ships and two sloops against him. Gill's six-hour fight rallied the townspeople and made the French withdraw without carrying out their design to burn and pillage the community.

In January 1705, St. John's was again attacked overland from Placentia. On this occasion, Subercase, the French commander, had a force of almost 500 regulars, French Canadians and Indians. He took the town, but the Fort William garrison held out and refused terms. After a five-week siege, Subercase retired to Placentia with all the booty his men and several hundred captive townspeople could carry. That summer, detachments of French and Indians attacked and burned out all English communities in Conception, Trinity and Bonavista Bays. Sporadic attacks continued throughout 1706, despite British reinforcement of the St. John's garrison. The British responded by deploying a small squadron of warships to harass French ships and fishing stations in the Notre Dame and White Bay areas: six French armed vessels and numerous fishing bases were destroyed.

Yet another overland attack on St. John's by St. Ovide de Brouillon in January 1709, met with complete and immediate success. The British garrison, demoralised and badly led, surrendered the fort after only a brief resistance, and the French, taking 300 prisoners with them, withdrew to Placentia after destroying all the fortifications around the harbour. Despite the evident success of the 1709 attack on St. John's, it is significant that outlying settlements were too strongly held for the French detachments sent against them to make any impression. The following year the British began rebuilding Fort William and emplaced stronger armament. French fishing stations in the North of the island were again attacked and destroyed by naval vessels sent out with the fishing fleet. No further attempts were made on the English settlements from the Placentia base and, in 1711, a large British naval and military force, comprising 15 ships and 4000 men, was sent to capture it. However, as on the previous occasions in 1692 and 1703, the attack was given up as impossible. By 1712, British victories in Europe had brought about an armistice and, in the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), the French yielded all rights in Newfoundland to Britain and were forced to leave Placentia.

Subsequently, the British fortifications in Newfoundland were neglected and fell into decay. Hence a major reconstruction was hastily begun when war with France was renewed in 1743. During "King George's War" (1743-48) no military action occurred in Newfoundland itself, but, since the time of Utrecht, the British had maintained a strengthened naval force in the colony as a counter to the elaborate fortress then established by the French at Louisbourg in Cape Breton. It was a naval squadron from the Newfoundland station which convoyed and supported the successful Anglo-American attack on Louisbourg in 1745.

Subsequently, the British fortifications in Newfoundland were neglected and fell into decay. Hence a major reconstruction was hastily begun when war with France was renewed in 1743. During "King George's War" (1743-48) no military action occurred in Newfoundland itself, but, since the time of Utrecht, the British had maintained a strengthened naval force in the colony as a counter to the elaborate fortress then established by the French at Louisbourg in Cape Breton. It was a naval squadron from the Newfoundland station which convoyed and supported the successful Anglo-American attack on Louisbourg in 1745.

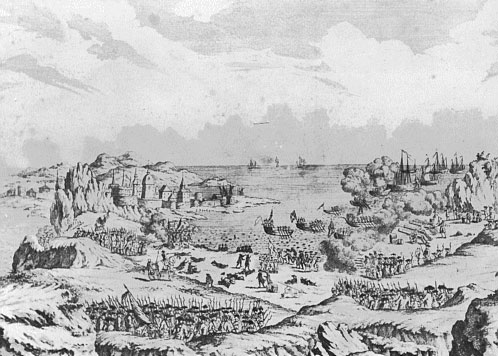

The final military engagement in Newfoundland occurred in the fall of 1762 and was the final action in the Anglo-French war of 1756-63 (The French and Indian War). As was the case in the conflict of 1743-48, hostilities in the French and Indian War were centred primarily in the Maritimes and Quebec. British victories at Louisbourg (1758), Quebec City (1759) and Montreal (1760) virtually eliminated the French presence in North America and led to the opening of peace negotiations under conditions of great disadvantage to France. Desperate to recover a bargaining counter, the French government dispatched a naval force with 800 troops to attack Newfoundland. Following earlier French-Canadian strategy, d'Haussonville, the French commander, marched overland on St. John's from a landing in the undefended harbour at Bay Bulls. The British garrison in Fort William, few in numbers and without well- prepared defences, made no resistance and surrendered on June 17th. The British Command in New York quickly organized a counterstroke. By September, 1500 regular and New England troops had been convoyed to the Avalon and, on September 13th, their commander, Lt. Col. William Amherst, made a landing at Torbay eight miles north of St. John's. Marching overland, Amherst drove the French from their outer defences at Quidi Vidi Pass and on the 15th captured the high ground of Signal Hill in a surprise dawn assault. With the French force now confined to Fort William, Amherst occupied the following two days bringing up heavy guns to reduce the fortifications: meanwhile, to the chagrin of the Royal Naval Commander, Lord Colville, the French warships which had convoyed d'Haussonville's force and which remained in St. John's harbour, escaped under cover of a thick fog. Amherst's batteries - one on the lower slope of Signal Hill and another north of the Fort on high ground along King's Bridge Road - were ready by the 17th and began an intensive bombardment of Fort William that day. Surrounded and unsupported, d'Haussonville's force capitulated on September 18th.

Amherst's successful campaign of 1762 brought to a close a century of armed conflict on Newfoundland soil. Thereafter, Newfoundland's war efforts were oriented toward imperial and commonwealth war services overseas.

Amherst's successful campaign of 1762 brought to a close a century of armed conflict on Newfoundland soil. Thereafter, Newfoundland's war efforts were oriented toward imperial and commonwealth war services overseas.

MILITARY OPERATIONS IN NEWFOUNDLAND 1662-1763

Naval Wars with Holland, 1652-74

1662 - French fortify Placentia.

1665 - Dutch fleet under Admiral De Ruyter captures and burns St. John's.

1673 - Capt. Martin's defence of St. John's against Dutch and pirate attacks.

War of the League of Augsburg, 1689-1697 (King William's War)

1692 - Abortive British attack on Placentia.

1694 - Capt. Holman's defence of Ferryland.

1695 - HMS Sapphire sunk at Bay Bulls.

1696 - French capture Bay Bulls, Petty Harbour and St. John's.

1697 - British troops reoccupy St. John's. Some 214 of 300 soldiers perished during winter due to lack of provisions, shelter, etc.

1698 - Construction begins of Fort William, completed by 1700. Orders given for the permanent garrisoning of St. John's.

War of the Spanish Succession, 1702-13 (Queen Anne's War)

1703 - Abortive British attack on Placentia.

1704 - Capt. Gill's defence of Bonavista.

1705 - French attack of St. John's but unable to take Fort William. All communities in Conception, Trinity and Bonavista Bays, with the exception of Carbonear Island, destroyed by the French.

1709 - French forces capture Fort William with little opposition. Over 300 English prisoners transported to France. All forts destroyed.

1711 - Abortive British attack on Placentia.

1713 - Treaty of Utrecht removes French from Placentia. Subsequently, British fortifications decay.

War of the Austrian Succession, 1743-48 (King George's War)

1743 - Major reconstruction of Fort William by British.

1745 - Naval squadron from Newfoundland sent to support successful Anglo-American attack on Louisbourg.

Seven Years War, 1756-63 (French and Indian War)

1762 - French capture Bay Bulls and St. John's in June. British Forces under command of Col. William Amherst recapture town in September.

1763 - Fort William rebuilt and construction begins on Queen's Battery, Crows Nest Battery and Fort Amherst. Treaty of Paris forces France to abandon all her possessions in North America except the Islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon and fishing rights on the north west coast of Newfoundland.

FOOTNOTE:

1. In 1975 the underwater wreck of HMS Sapphire was declared a Provincial Historic Site and archaeological excavations have yielded significant artifacts, some of which are now in the collection of the Newfoundland Museum.