William Winter: The Man Who Made The Furniture

William Winter: The Man Who Made The Furniture

By Cynthia Boyd

Winter, 1991

[Originally published in printed form]

Since the publication of Conception Bay Furniture Maker (Museum Notes, No. 9), further research has been done on the furniture making business of William Winter. Interviews with residents of Clarke's Beach and neighbouring Conception Bay communities and with family members living as far away as San Francisco brought forth additional information about, and insightful commentary on, the life and craftsmanship of this productive individual. This essay offers a brief analysis of Winter's furniture, drawing on information obtained from both earlier and more recent research.

Since the publication of Conception Bay Furniture Maker (Museum Notes, No. 9), further research has been done on the furniture making business of William Winter. Interviews with residents of Clarke's Beach and neighbouring Conception Bay communities and with family members living as far away as San Francisco brought forth additional information about, and insightful commentary on, the life and craftsmanship of this productive individual. This essay offers a brief analysis of Winter's furniture, drawing on information obtained from both earlier and more recent research.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Winter constructed hundreds of pieces of furniture for the bedroom, kitchen, and parlour that resembled contemporary factory-made furniture. While Winter's furniture was similar in its basic form and design to pieces being mass-produced, his repertoire of decorative and ornamental embellishments gave his work a character all its own. Winter likely borrowed many or all of these decorative techniques from those found in catalogues, books of instruction, or from furniture in the shops of Harbour Grace and St. John's. What makes Winter's embellishments unique to his furniture is the way in which he combines the decorative details and applies them to various pieces of furniture.

Winter is perhaps best-known for his parlour pieces, especially his sideboards, many of which are still in use in homes around Conception Bay. A typical parlour sideboard (plate 1) consists of two sections: on the bottom is a cupboard enclosed by two doors, over which is built a single drawer; on the top is a high backboard with a centred mirror. Typically found above the mirror is a length-wise shelf for displaying glassware and knick-knacks. One unusual feature perhaps unique to Winter's work is an open shelf that has the appearance of a long step leading from the rear of the top of the cupboard section to the bottom of the mirror. Generally, Winter's sideboards are made of pine with an applied finish that resembles mahogany. By painting and/or carving a leaf- like ornamentation on the front of the cupboard doors and drawers and then applying a fine line of yellow paint along the edges of panels, drawers, and doors, Winter gave the sideboard a "finished look". Although, winter used this basic plan from one sideboard to the next, he individualized the pieces through the use of decorative embellishments.

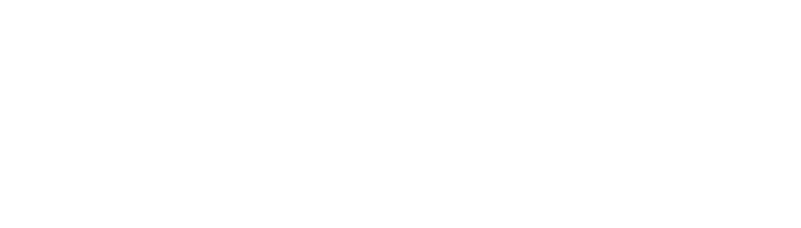

A recently acquired sideboard (plate 2) in the Newfoundland Museum collection suggests that Winter varied his decorative techniques much more than was originally thought. Although the basic construction is characteristic of other sideboards, there are several peculiarities that make this particular piece distinct. The base, for instance, has two tiers of drawers rather than the usual one. Furthermore, unlike other Winter sideboards, the drawer fronts are not rounded. Instead, they are left flat and incised with a spring-leaf motif - a decorative device Winter commonly employed on many of his furniture forms, for example, on the backs and aprons of his parlour chairs (plate 3) and couches. Finally, in place of Winter's plainly turned shelf supports, this sideboard has supports that are much more decorative, in fact, the shape of these pilasters is similar to the decorations flanking the door of a record cabinet also made by Winter.  Winter diversified the form and decoration of his furniture models to varying degrees. Perhaps this was done to offer a potential buyer the opportunity to choose something more suited to his/her specific taste or economic means. His sons, William and Nicholas both claim that "for a few extra dollars..." their father would make, as requested, additions or changes to any given furniture model. Winter also did work on commission as exemplified by an elaborate sideboard made for the Roman Catholic rectory in Brigus, which is now part of the Museum's collection. One can also speculate that Winter's need to create different combinations of decorative embellishments may have been a result of playfulness and experimentation in furniture making. Gerald Pocius notes this tendency toward experimentation in his research on Newfoundland furniture makers of Bonavista Bay.

Winter diversified the form and decoration of his furniture models to varying degrees. Perhaps this was done to offer a potential buyer the opportunity to choose something more suited to his/her specific taste or economic means. His sons, William and Nicholas both claim that "for a few extra dollars..." their father would make, as requested, additions or changes to any given furniture model. Winter also did work on commission as exemplified by an elaborate sideboard made for the Roman Catholic rectory in Brigus, which is now part of the Museum's collection. One can also speculate that Winter's need to create different combinations of decorative embellishments may have been a result of playfulness and experimentation in furniture making. Gerald Pocius notes this tendency toward experimentation in his research on Newfoundland furniture makers of Bonavista Bay.

While Winter's sideboards were made in different versions, his matching bedroom bureau and washstand sets, on the other hand, are all very similar in both form and decoration. These sets have lyre-shaped backboards which, on the bureau, support a mirror and, on the washstand, hold a towel rail. Unlike most of his furniture, Winter's bedroom sets are not generously decorated. They were made for bedrooms which were the most private rooms of the house and, therefore, were not seen by everyone who happened to visit. Bedroom sets were designed more for utility and less for impressive display.

Until recently, the only type of Winter washstand reported was the one just discussed. The Museum, however, has now acquired an entirely different form of washstand (plate 4) made by Winter. This piece has splashboards rather than a lyre-shaped backboard, and the decorative features include applied rectangles with scooped corners (a decoration Winter also used on his lyre-back washstands), a rounded drawer front, split balusters and a crowning rolling pin or baluster.

Until recently, the only type of Winter washstand reported was the one just discussed. The Museum, however, has now acquired an entirely different form of washstand (plate 4) made by Winter. This piece has splashboards rather than a lyre-shaped backboard, and the decorative features include applied rectangles with scooped corners (a decoration Winter also used on his lyre-back washstands), a rounded drawer front, split balusters and a crowning rolling pin or baluster.

Nick Winter recalled that on one occasion his father altered a particular ornamental feature due to an accident. Distinctive to Winter's earlier parlour couches were carved dog-heads adorning the back of the couch. As Winter had trained his dog to run within the treadmill of a large lathe, which turned the wood into different parts of furniture, perhaps this decoration was a tribute to such an amazing canine. Winter shipped many of these couches to Bell Island, and while transporting the furniture by box cart to the dock, Nick and his father encountered some difficulty with their horse. The nervous animal's sudden movements shifted the load in the cart and as a result, the dog-head ornamentation on the couch was broken off. Because it had to be shipped that day, Winter simply sanded down the broken edge and revarnished it. Few of Winter's couches in existence today include this dog-head decoration; possibly its accidental removal created a simple ornament that took less time and appealed to Winter. On the other hand, the dog who turned the lathe died and perhaps with him this decorative detail.

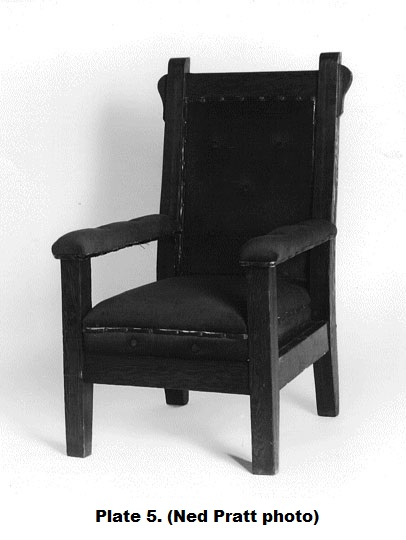

After William Winter's death in 1936, Nick Winter took over his father's business on a part-time basis. Like his father before him, he constructed a general line of furniture which he sold to residents of Conception Bay including Bell Island. Although he continued to use his father's templates or "molds", the economic realities of the time restricted him from lavishing on his products the degree of ornamentation that characterized his father's furniture. In fact, the amount of embellishment Nick used diminished with time. On many occasions, for example, Nick found that the varnish he had applied to his bedroom sets was of inferior quality. After the sets had been sold to his customers, the varnish bubbled and cracked and, consequently, the finish had to be replaced. Nick's furniture, while much plainer than his father's for the reasons mentioned, shows the influence of William Winter. An example of his work is a chair (plate 5) which is the only surviving part of a parlour set. Typically such sets consisted of a settee, rocker, and arm chair. While William Winter's parlour chair is more delicate in appearance and is generously decorated with incised sprig-leaf motifs, Nick's chair has only one applied decoration: brackets or "ears" which are commonly seen on similar parlour chairs made circa 1900.

Many people from neighbouring Conception Bay communities hand-crafted their own furniture because they could not afford to buy it. In making furniture themselves without any formal training, these rural craftsmen modeled their work from that made by local furniture makers like William Winter. Furniture made and found in this area provides evidence that craftsmen were influenced by Winter because they applied similar decorative details, such as sprig-leaf motifs and split turnings, that were characteristic features of his furniture.

It is encouraging that pieces of Winter's furniture continue to be used in at least a half dozen homes in the general area of Clarke's Beach. On some occasions when furniture was being photographed in their homes, people would describe how a sideboard or a dresser had been located in that particular corner of the house since it was first brought into the home. This information is significant in that Newfoundland outport furniture was commonly associated with hard economic times of pre-confederation days and therefore, was usually destroyed. More recently, people have begun to recognize their Newfoundland heritage, and are holding onto artifacts like outport furniture, that are physical representations of Newfoundland's historical and cultural past. The craft and craftsmanship of William Winter is a lasting legacy of Newfoundland's rural furniture-making heritage.

It is encouraging that pieces of Winter's furniture continue to be used in at least a half dozen homes in the general area of Clarke's Beach. On some occasions when furniture was being photographed in their homes, people would describe how a sideboard or a dresser had been located in that particular corner of the house since it was first brought into the home. This information is significant in that Newfoundland outport furniture was commonly associated with hard economic times of pre-confederation days and therefore, was usually destroyed. More recently, people have begun to recognize their Newfoundland heritage, and are holding onto artifacts like outport furniture, that are physical representations of Newfoundland's historical and cultural past. The craft and craftsmanship of William Winter is a lasting legacy of Newfoundland's rural furniture-making heritage.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Pocius, Gerald L. "Gossip, Rhetoric, and Objects: A Sociolinguistic Approach to Newfoundland Furniture." In Gerald W.R. Ward ed. Perspectives on American Furniture, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1988, pp. 303-345.